Corners of the Internet #4

Caplan and Lehmann on work & happiness, Strauss on Zoomers, Klosterman on the Nineties, Russell on expectations, Henderson on cooperation, Douthat blast from the past (again)

A friend and early blog reader once told me I seemed to know all the interesting corners of the internet. In the spirit of that compliment, COTI is a loose format for sharing what I find in these corners.

In a podcast conversation with Rob Wiblin, Bryan Caplan praises the emotional benefits of work,

One really great point that Tyler Cowen has made is that if you think about people who are in very poor families, very often their families are dysfunctional, and their job is the one place where they can go to where it’s orderly. At home there may be great family strife, alcohol problems, drug problems, someone’s unemployed and is mad about it, the teenage girl is pregnant, and the family is really upset and doesn’t know what to do. And then someone from one of these families can go and work at McDonald’s, and here things are running like clockwork — and it’s actually a comfort to a lot of people to be in such an orderly place.

When I was in Costa Rica, I went to an area that I will describe as fairly frightening. It was Limon. Now the trash problem was so bad in Limon that ‘d say the average depth of trash in the streets was about six inches. So basically if you just walked in the streets, you would be walking in trash. They had a very nice, modern McDonald’s there, and one of the tour guides was saying that was the best place in town just to go hang out. Now of course, working and hanging out aren’t the same, but if it’s the very best place to hang out, sounds like it’s one of the better places to work as well. At least you’re around people who are happy, and you just interact with people who are feeling there’s something positive going on in their lives.

Claire Lehmann makes a similar connection between work and well-being, drawing on her early experiences in the service industry:

We often feel anxious and depressed when we’re focusing on ourselves too much and we’re ruminating and we’re thinking about when we get trapped in our own mind and in our own world so focusing on what we can do for others is an easy way to get out of that trap. . .

I worked before I was doing a psychology masters and before I began doing Quillette, I worked for 10 years from the age of 15 to 25 as a waitress, and I think that was actually probably one of the best things I’ve done in my life because, I remember being in my late teens and early twenties and just having all of these interactions with people. . . every week having hundreds of interactions, small interactions where you have to greet people, seat them, take their order, attend to them during their dinner, and make sure everything’s ok. They’re just tiny, small interactions but any social anxieties become immediately extinct and you learn confidence in just talking to people and any kind of fear you have as a young person who doesn’t have high status, doesn’t have much experience in the world, that all sort of melts away just from having a service job. And I think having a service job is one of the best things a young person can do.

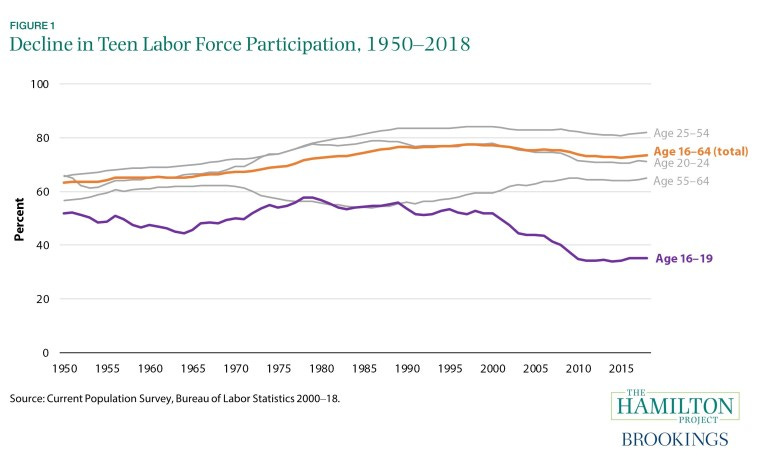

Even before Covid, increasing anxiety among Gen Z was alarming. Might teen exodus from the workforce have something to do with it?

Yet even the apparent dream job of a professional athlete seems remarkably prone to broader trends in declining happiness. Pointing to many examples of miserable stars, Ethan Strauss writes,

Don’t be surprised if the next decade is replete with athletes rising fast, only to declare themselves miserable in public.

Elsewhere, Strauss interviews Chuck Klosterman on the Nineties. I particularly recommend the discussion from 30:30-42:00.

Recent research suggests women have suffered especially marked declines in well-being recently, in line with longer-term trends. Drawing from her personal experience, N. Russell writes,

When I tried to relate to other girls, I felt like I was signing up for a losing team. But I also grew up in the era of “toxic masculinity,” so when I tried to relate to boys, I felt a suspicion and a defensiveness that served my friendships poorly. At work, it was easy for me to blame social slights on the fact that I was the only woman in the office, instead of maybe as spurs to self-improvement. I was taught that I could learn and achieve anything, and I believed this was true. But all the speechifying I’d endured about power imbalances and pervasive sexism also created bleak expectations for my personal life.

More generally, fixation on group-based grievances has always struck me as an obstacle to building trusting relationships. New substacker Rob Henderson writes,

Gambetta observes that using revealed preference in the case of cooperation is an error. We might infer that if cooperation doesn’t come about, then that means people actually prefer the lack of it.

But this is wrong.

What is actually lacking is the belief that everyone else is going to cooperate. People are worried about being the only “sucker.” So they defect because they think that’s what everyone else does.

No one wants to cooperate if they believe everyone else is going to defect.

In the world of traditional news, The Wall Street Journal reports,

All children should be screened for anxiety starting as young as 8 years old, government-backed experts recommended, providing fresh guidance as doctors and parents warn of a worsening mental-health crisis among young people in the pandemic’s wake.

The draft guidance marks the first time the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has made a recommendation on screening children and adolescents for anxiety. The task force, a panel of independent, volunteer experts that makes recommendations on matters such as screening for diabetes and cancer, also reiterated on Tuesday its 2016 guidance that children between ages 12 and 18 years old should be screened for major depressive disorder.

Will screenings stem the tide of worsening suicide and declining mental health? Who knows. Of the 78 studies examined by the experts mentioned, not one tested the effect of screening against the null hypothesis.

Ten years ago this week, Ross Douthat wrote,

The United States has witnessed a hundredfold increase in the number of professional caregivers since 1950. Our society boasts 77,000 clinical psychologists, 192,000 clinical social workers, 105,000 mental health counselors, 50,000 marriage and family therapists, 17,000 nurse psychotherapists, 30,000 life coaches—and hundreds of thousands of nonclinical social workers and substance abuse counselors as well. “Most of these professionals spend their days helping people cope with everyday life problems,” Dworkin writes, “not true mental illness.” This means that “under our very noses a revolution has occurred in the personal dimension of life, such that millions of Americans must now pay professionals to listen to their everyday life problems.”

On the one hand, as Kaplan says, work provides structure that we can lean on if our lives are lacking one.

On the other, when people rely entirely on work to provide them with a sense of life and structure, unwanted effects like the Woke movement occur. Daren Paul put it well: "In decades past, Americans would express and advocate for their cultural values through their churches, fraternal organizations, charities and clubs. As such institutions declined since at least the 1990's, the workplace emerged as the most important-and for many, the only-site of popular sociocultural action. "

The culture of therapy that Douthat describes is related to what happens in the workplace. Again Daren Paul: "In fact woke capital is the epitome of two intertwined developments in the American political economy since the 1960s: globalized corporate power and a national therapeutic culture. (...) narratives of suffering and healing, of authenticity and liberation, of self-care and self-actualization, overflow the fields of psychiatry, psychology, and counseling to fill schools, churches, corporations, and the state. It stands today as our national collective moral philosophy."

Link to Paul's essay: https://wesleyyang.substack.com/p/woke-capital-in-the-twenty-first?s=r

> similar connection between work and well-being

It is one of the main "solus populi" ideas for the working and lower middle class, but here be the problem: the liberal arts barista class really need ways to be artists rather than power-hacking bureaucrats, and they are not suited to the service industry as they are often "crazy enough to do art" but not mentally stable enough to handle people. Are there easy solutions for this other than Etsy-fication?