Co-founder Hamish McKenzie writes,

In the summer of 2018, I met a freelance journalist named Luke O’Neil at an exposed-brick bar in Boston. I was there to convince him to start a newsletter. Luke’s friend Judd Legum, who had recently started Popular Information, thought Luke could do well on Substack because of his distinctive voice, cracked sense of humor, and livewire Twitter presence. Luke wore a fitted baseball cap and smoked cigarettes as if it were 1994. Tattoos crawled over his arms.

Over cocktails, I gave him my best pitch:

Stop taking on freelance assignments that you don’t like.

Write what you want to write.

Get paid directly by your readers.

The post tells the story of Luke’s early success and subsequent falling out with Substack. I would encourage you to read the whole thing.

A few highlights/thoughts:

1:

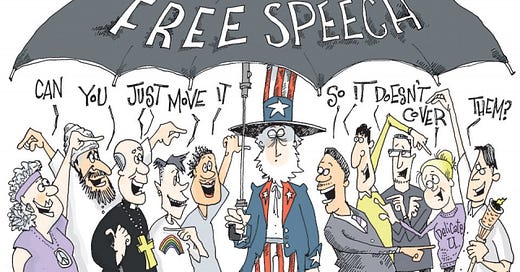

In the early years of Substack, most of the high-profile writers were left-wingers like Luke. Defending speech meant standing on the opposite side of Fox News. That was 2019.

Chris and I flew Luke to New York for a night of drinks. He almost couldn’t believe how well it was all going. We had a good night together, but he retained his fierce independence. A few IPAs in, he told us that if Substack ever fucked up, he’d be letting us know. He hoped we wouldn’t ever let “bad people” on the platform. I pressed him on what he meant, and he said if Ben Shapiro ever turned up on Substack we’d be going in the wrong direction.

2:

The inevitable falling out provides a nice illustration of asymmetric insight.

“I always said I was going to tell you if you were fucking up,” Luke said over the phone. “Well, you’re fucking up.”

We had a strong relationship and had always spoken frankly with each other. I appreciated that he was airing his criticism with me directly and privately. But two things he said on that call have stuck with me. One was that he was “almost embarrassed” that my endorsement was on the cover of his latest book, Lockdown in Hell World, a second volume of his Substack writings. The other was that he thought that Chris, Jairaj, and I were just chasing money, evidenced by us raising funds from venture capitalists and then embarking on the Pro program.

“You just want to get rich,” he said. “Admit it.”

I didn’t like that. I had not got into Substack to make money. In fact, when Chris first proposed starting a company together in 2017, I resisted the idea. I knew that life as a startup founder would be stressful and an unrelenting grind. I never imagined myself as a businessman. I wanted to be a writer. I was plotting a future for myself as a freelancer, with the hope of writing books and perhaps getting speaking gigs to cover living costs. My wife Steph and I were just about to have our first kid and I wanted to be a good, available father, in control of my own schedule and not too bogged down by the demands of work. I also knew that most startups fail – especially media-focused startups. I had covered many such startups as a reporter for PandoDaily in 2012 and 2013 and saw dreams crushed as Silicon Valley tried and failed to “save the media.” In all cases, it was writers who were hurt the most along the way.

Luke claims to know McKenzie’s inner feelings better than he does, which exacerbates the conflict between them. Though self-deception and hypocrisy are genuine features of human nature, it is generally better to focus on ways you may be deceiving yourself than attempt to pick them out in others.

3:

The comments on Luke’s departure post show why opposing censoriousness is an uphill battle. A small number of voices strongly committed to outrage can place a lot of pressure on creators to condemn opposing views and switch platforms, while those inclined toward toleration will continue to subscribe either way. The most intolerant wins.

4:

One cool feature of Substack is that writers can easily move their subscriber list to other platforms.

When I finally got the “goodbye” email, I had the wind taken out of me. But by that point, there was nothing more I could do. He didn’t like the vibes here.

I remain deeply sad that Luke isn’t publishing on Substack anymore, but I am happy he had the power to leave. That agency has been a crucial missing piece from the systems that writers have worked within for decades. I know, because I’ve lived that life.

Including this feature also serves as a kind of pre-commitment—if Substack falls short of its reputation for free expression, existing talent can jump ship.

5:

While it’s pretty clear I take Substack’s side on this issue, I’m not without sympathy for Luke. It’s not 1977 anymore.

Back then letting the Nazis speak entailed small and sporadic marches in faraway towns, not having their views paraded before you on social media.

But while preserving free speech in this environment undeniably comes with a higher price, I’m glad Substack is willing to pay it.