Time Well Spent: An interview with Sotonye Jack

Why internet fame is the least unequal form of inequality, how to be a Torah Maximalist, and whether modern Judaism remains distinct from Christianity. Plus he makes me an offer I can't refuse.

Sotonye Jack is the creator of Time Well Spent, a delightful newsletter that is home to some of my favorite long-form written interviews. He has also written beautifully about his religious experience as a recent convert to Judaism, which I really enjoyed learning more about. After wrapping up the interview, Sotonye invited me to contribute regular posts on his platform, with free reign to comment on more or less whatever I want. What more could an infovore ask for?

Check out my first post as a TWS contributor here, and enjoy the interview!

Info: Something that’s stuck with me from the first time I read you is the idea that the internet has brought everyone into a hypercompetitive ranking system, “a global tournament of interestingness”, that seems to direct an increasingly large share of our attention away from the people around us and concentrate it in a very small number of far away internet people. As a famous internet person yourself now, what do you make of this trend toward greater attention inequality?

Sotonye: I want to focus on the bit about the internet shifting attention away from those around us before I get to your question, since this is something I’ve been thinking about over the last few days.

I saw a young woman tell a story recently where she was taking her usual walk around her city when an older woman approached her, asked for her name, and followed with a battery of personal questions. The girl was weirded out by the exchange but, since the woman seemed harmless, she had no real issue playing along, not knowing exactly where this was going, but again feeling some level of unease all the while.

They started walking together and talking a bit more, and the girl began to share some of her interests with the older woman, which centered mostly around non-traditional paths toward health and her skepticism of modern medicine. The girl believed that we should do everything in our power to improve our heath on our own before seeking recourse in drugs, and the older lady soundly agreed. The girl recommended that the lady look more into the topic online but, to the girl’s shock and amusement, the old lady said she didn’t have a smartphone or a computer.

The girl said to herself, “This is the reason why this encounter happened to begin with.” She thought about how almost no smartphone user would ever interpolate themselves into her day the way the old woman did, it broke the fundamentals of phone-culture etiquette, and she had never experienced anything like it. I assume that 90% of her interactions with friends and family happen online and all the courtship she’s experienced outside of high school has been online. She was shocked that an interaction started without mediation by the internet. If you want to talk to anyone you follow them and send a dm, these are the new rules of propriety which the old woman knew nothing about, and the girl found it deeply refreshing.

The old woman in the girl’s story reminded me of how I felt up till I turned around 24 years old, three years ago. I used to want to never use a phone ever again around that time and I thought the need was extremely embarrassing; having to talk to someone through a keyboard instead of in person felt shameful and inhuman. There was some soul missing, both my own and the soul of whomever I tried to talk to, and I think a fair share felt that way too around then. I remember there was this blonde girl I met on Twitter, model girl. I plotted to charm her and steal her heart right out of her hands, and it worked. But she was perfectly fine texting all day and I just wanted to see her. I didn’t understand this weird behavior I thought she exhibited, it seemed like her mind was misshapen.

It was like she had no energy to see anyone in person, and even keeping interactions going over text was too much, but even so that was all she could bear. Maybe it was anxiety, I thought. And I would ask about it, but it didn’t seem she really understood the problem herself. She knew there was something wrong, she knew that she should want to spend more time in person. There was still some residual feeling of the world before phones, I represented that world and wanted to draw her into it. But she couldn’t really manage it.

And as of lately, I’ve been feeling warped in the way that she was, in the way we all are now. It took several times longer for the same to happen to me, but it did happen. Now I feel that I have no energy for people in real life, and even texting is too much to bear, but it’s the only thing that will do. I hate being this way, especially since I remember now what a Luddite I was, and I’m craving escape from this cyber trap again.

My phone is not more entertaining than anyone on earth, but the pleasure is so much easier to seize. I’ve curated a private world to satisfy every single one of my interests, it’s nearly perfect and completely immediate. And not only that, all of my business is online. There’s never any reason to look up from my phone. But I hate that. When you look at yourself in third person, sitting in one place, staring silently at your phone, you don’t see an inspiring figure or person you can respect, that’s not someone with a grand destiny. It’s a cliche to say but you’re plugged into a cordless matrix. I want more, I want my obsession to be other people again. I’m starting to hate the internet.

Of course there are some benefits though, like being on the positive end of internet attention inequality, to get to your question. And I think this is the least unequal form of inequality I’ve seen in my lifetime, and perhaps the least unequal form that’s existed in history. Fame is no longer reserved for those in the 90th percentile of intelligence or ability, fame is now the domain of the middling and above. Even those on the lower bounds of cognitive ability and talent can get ahead if they’re simply diligent. If you post consistently, you can gain a following. I’ve never seen anything like this. Every young person I see online sort of has an air of someone who thinks they can be famous, despite not having any interests in anything or any special talents. And they’re right, they can be.

Not everyone will be famous of course, but the internet has dramatically increased the proportion of the undeservedly popular and wealthy. There are more people than ever before who boggle our minds because of the trivial real world value of their work and their obscene concomitant status and prosperity. The YouTuber, the TikTok dancer, the instagram model, the Twitter personality. We can hate it, but it’s still pretty cool.

Info: Reading over some of your recent posts, I was reminded of a quote by Thomas Sowell:

“Much of the social history of the Western world, over the past three decades, has been a history of replacing what worked with what sounded good.”

On what particular issues do you most agree with this statement and on which might you disagree? Feel free to adjust the time frame as needed.

Sotonye: Here are some recent issues where I agree with Sowell:

Defunding the police and prison abolition.

These ideas sound great, and it would be very nice to have a world where we didn’t need state agents with license to kill, or cages to throw men in. But violence is a human universal, the indelible story of our past and our future. Taking away the state’s monopoly on violence would just leave a vacuum that wouldn’t have the legal directives, financial incentives, and oversight that turn such violence into an underrated social good. That doesn’t mean police can’t mess up. It just means police follies are an easy tradeoff relative to the alternative.

And of course it sounds great to not lock people away in filthy cages, depriving them of their rights and dignity. But then you see that half of all state inmates are in for violent offenses like murder, and prisons start to seem self-explanatory. And then you see reports from the United States Sentencing Commission showing, in a sample of 10,000 violent federal offenders, that nearly 64% recidivated at a median of about 18 months after release. There are people that can’t participate in civil society, and it would be a great injustice to allow them to. You, your family, your neighbors, all the children in your neighborhood, all the children in the nation, they all deserve to never face threats of violence in their lives. I would want much worse than just prison for anyone who threatens the innocent. Prison abolition is a weird idea.

Next would be traditional gender roles.

It sounds like a great idea to simply dispense with them, since everything is just socially constructed right? Well no. This is where the egalitarian paradox shows what a disservice the concerted effort to minimize differences between men and women has been.

An egalitarian society is one where much time and effort has gone into ensuring all opportunities are open to everyone, regardless of sex or any other characteristic. But the most egalitarian societies see the largest sex differences in personality and the most significant self-segregation of the sexes in life outcomes, with most women selecting into traditionally feminine college and career paths, and with most men choosing traditionally masculine paths in college and in their careers. I recently saw an article from the New York Times I believe that claimed that the “maternal instinct,” the motherly, warm, compassionate, sensitive streak in women, is a social construct, a recent male invention. Data published by the Department of Education on bachelor degrees earned by women by field shows that around 50% of the degrees women obtained 2018-19 were in domains of “caring,” with some examples being health (which was the most popular field overall by far), psychology, education, and social services. When women have free choice, they behave suspiciously in line with traditional ideas about gender. Attempts to persuade men and women that there’s no sexual dimorphism in behavior is just an attempt to discourage what people naturally tend to like. It’s not very nice.

Lastly would be the colorblind orientation to race.

When I grew up I thought the coolest thing in the world was that I would be judged by my merit and not by how I look, it seemed like the best practice for a multicultural civilization. But now that’s been thrown out the window, with the reason being that, since certain groups have suffered past harm, mostly from whites, that it’s justified to employ positive discrimination, to judge on the basis of skin color in order to benefit some people. And this sounds great to some folks, mostly in the upper crusts of academia. But it doesn’t sound good to me for reasons which I think are obvious. Selecting anyone on the basis of anything besides merit is a great way to create institutions that fail quickly. We all want institutions that work, the only way to have working institutions is to find and promote the best people. A society that promotes people on the basis of race is not one that will last very long.

A place where I disagree with Sowell would be Christianity.

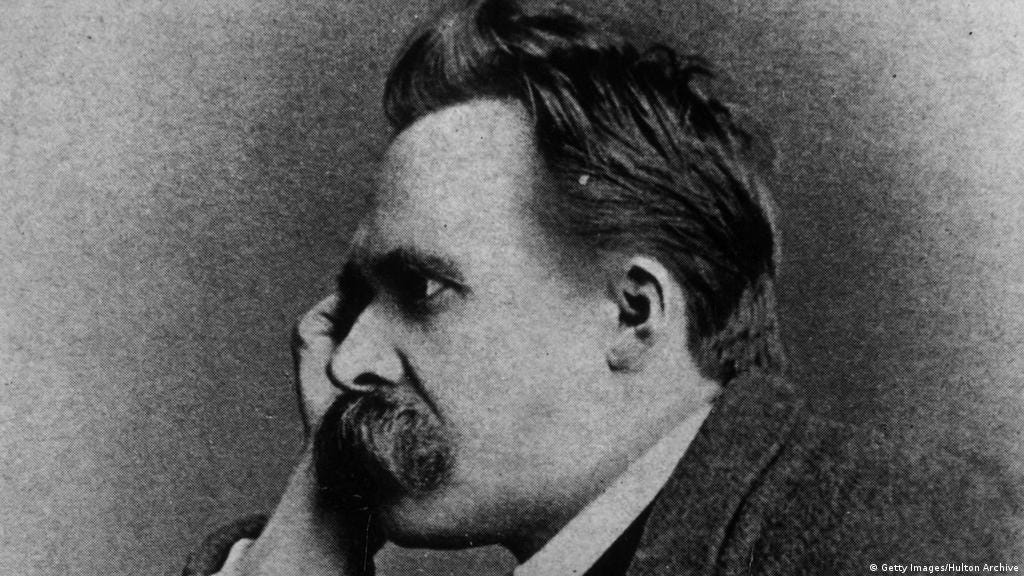

A new consensus has grown over the last decade and a half that views Christianity as a poor compass for our morals, and I agree with the sentiment, just not for the reasons normally used to advance this idea, which are typically rooted in relativism. All I’ll say here is that Nietzsche has the right idea about Christianity and Christian morality. He’s necessary reading I think for everyone.

Info: About 1% of Americans are Jewish, and of those, about 1% identify as black. That puts you in the .01%! What was it like for you socially to convert to Judaism, without blood relatives or robust cultural connections within the faith?

Sotonye: I’ve always been known for being abnormally independent, so the people in my life really didn’t think anything of my converting. But a decent part of my online community didn’t take it so well. I lost maybe 200-300 followers on Twitter after I announced my plans to convert. A lot of this was my fault though, since a sizable portion of the people in my area of Twitter are Christian, and I spent a lot of time online telling them about why they’re wrong. But most of those guys are cool and we still get along today even if we vehemently disagree.

Info: You’ve described your approach to religious study as Torah Maximalism, more in line with the sadducees and karaites than with rabbinical Judaism. I also noticed that your name (pseudonym?) means God’s will or purpose. What do these descriptors mean to you personally and in what ways does your day to day faith practice stem from these beliefs?

Sotonye: For those who don’t know, the three main branches of Judaism today are called Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism, and Orthodox Judaism. Each branch finds its root in the rabbinic tradition which began not long after the center of Jewish life, the Jerusalem temple, was destroyed in 70 CE in a war between Jews and Rome. Rabbinic Judaism draws its authority from a 2nd century compilation of oral laws called the Mishna—which is a rabbinic commentary on the 5 Books of Moses—and a commentary on the Mishna called the Gemara, compiled between the 2nd and 6th centuries. Both the Mishna and the Gemara together make up a work known as the Talmud. The main religious guide in Judaism is the Torah, the 5 Books of Moses, but, in rabbinic Judaism, the Talmud is viewed as the only means of understanding the Torah. And the laws in the Talmud are taken to be more or less immutable and equivalent to the laws given to Moses at Sinai. A Karaite is someone who thinks that only the laws of Moses are immutable, and everything else should be a matter of personal scrutiny. Rabbinic Judaism is a hand-me-down understanding of the Torah, and Karaism just doesn’t want to take things at face value. Karaism also believes the Torah to be peerless, and this is what I believe. I study the Gemara often, but in my opinion nothing is divine on the face of the earth besides the Torah.

But still, a lot of my daily practice is inspired by rabbinic Judaism, since I think the old sages were right about a lot. For example, there’s no place to bring sacrifices anymore due to the destruction of the temple, and the old sages say that Torah study and charity are equivalent to sacrifice. So I make an effort to put a few hours of Torah study in everyday and to donate as often as possible to charities in Los Angeles and elsewhere. The sages also say that the temple was destroyed because of this moral failing called Lashon Hara, or evil speech, which is basically speaking negatively about other people when you don’t have to, when they’ve done nothing wrong to you. And while I’m not sure this was why the temple was destroyed, I do think the sentiment is correct, that speaking ill of others as if I’m not equally as guilty is a terrible use of my power of speech, and it’s also arrogant.

The rest of my daily practices I get from the Torah, eating kosher, trying my best not to murder anyone.

(Also my name really is Sotonye, it’s Nigerian as you know and my dad is from there. I’ve always thought it was ironic that it means God’s will.)

Info: What do you make of the view that Judaism as we know it today has been highly influenced by Christianity? Listening to some of your answers, I see quite a few features I tend to identify with Christian doctrines:

Most obviously there’s replacing of animal sacrifice with more internal and service-oriented forms of religious devotion. There’s also a semblance of the idea that we’re all sort of sinners in a sense that softens the impulse to judge others too harshly. I see a fair bit of individualism that seems less pronounced in the Torah, and even features of Karaism you emphasize seem pretty consonant with the protestant idea of “sola scriptura” (though I realize that the historical Karaite movement goes back much farther than Luther).

Is there any sense in which you may in fact be practicing aspects of Christianity while rejecting some specific manifestations of it?

Sotonye: I think a few foundational ideas need to be established to demarcate the difference between Judaism and Christianity—the comparisons drawn here are often made by those who haven’t read much Torah or rabbinic literature, and so they suffer a dearth of critical ground on which to make their appraisals. There is a stronger comparison to be made between the rabbinic worldview and the Christian one than between the Jewish understanding of atonement and the Christian one, which I’ll get to later. But for now I’ll lay out a few key points in the Torah model of the world to illustrate the distinction from Christianity:

The first principle is that there is no original sin in Judaism, we aren’t born with sin, we’re born wholly good; sin doesn’t come until we commit certain actions later. Sin is also not impossible to prevent, which I think is a prominent Christian idea, that sin is an inescapable fact of life. But rightness in Judaism is a matter of keeping Ten Commandments which are so simple to keep that most people on earth keep most of them by accident. Most people don’t kill, steal, disrespect their parents, accuse others of things they haven’t done, bang anyone else’s wife, swear falsely by the name of God, etc etc. Being righteous in Christianity was only possible for one person, but righteousness in Judaism is possible for everyone, and though there will be some lapses and have been, sin is not an inescapable reality. Which gets me to my next point:

Atonement. When I mentioned sacrifices and how they’re no longer possible to make in the temple, and that they require a placement, it’s important to understand the reasons they were made to begin with. The first reason is not atonement. In the Jewish worldview, God has provided human beings with such goodness, such bounty, that not returning some of that goodness is a moral outrage. So when I say that Torah study and charity are equivalent to sacrifice, I mean this is my way of returning what the Holy One has done for me. He has lifted me up beyond anything I’ve been able to manage to do for myself, and there’s a saying the sages make, “God wants the heart,” which is a common idea throughout the Torah, so I give him my heart, commit my mind to nothing but His utter greatness, compassion, perfection. And I also give as much money as I can to those in need to honor what He’s done for me as well.

The second reason why sacrifices were made to begin with has to do with both unintentional sins and the proximity between God and the people who committed these accidental missteps. During the institution of the levitical system of sacrifice, God intended to live among the nation of Israel, which required special care which would not have been necessary otherwise. In the book of Exodus there’s a good illustration:

The Israelites just committed the golden calf incident, where God commanded Israel to not worship objects and they made an object to worship anyway, owing to the idolatrous habits formed in Egypt, and God said to Moses that He would not go along further in Israel’s midst as He had been, otherwise He would wipe them out. The idea is that God’s presence is so holy and awesome and beautiful, to stand in it requires outstanding care and presents genuine risk of death. In the book of Numbers the Israelites freak out and say they’re all going to die due to the danger presented by this extreme degree of holiness. They feared that anyone who goes near His abode, the Tent of Meeting, would surely perish. God eases the Israelites’ concerns by saying only Aaron and his sons will bear the guilt of standing too close to His presence. Being around God shifts circumstances beyond normal, as when Moses was commanded to remove his shoes at the encounter with the burning bush because where he stood was holy. Holiness necessitates sacrifice.

And sacrifices were only really instituted for accidental wrongdoings committed by people living in God’s midst, there’s no mention of the need for sacrifices in the Levitical system outside of thoughtless mistakes except in the narrow case of someone defrauding someone else and lying about it—intentional missteps require something else. Later in Leviticus, the method of atonement for intentional wrongdoing is described as remorse. God describes a situation in which He will bring suffering on one who has taken up against Him and His laws with increasing vigor. He goes on to explain that, when the rebellious individual finally staves his rebellion and humbles himself, he will be forgiven, his fortunes will be returned, all the suffering brought on him will be undone. There is no action that can commute an intentional sin in Judaism besides remorse, and the fact that the individual can expiate his wrongdoing at all without the need for a sacrifice is a key difference between Christianity and Judaism. There is no way to expiate sin in Christianity without sacrifice, it’s the central premise of the whole Christian project.

Later rabbinic Judaism however has been influenced heavily by Christianity in my opinion, not in any ways that diminish the distinctness of the two religions, but in ways that make comparisons more tenable. Christianity centers itself on the afterlife like a lot of other religions, the afterlife is everything. Human life is only a flicker of time on the cusp of yawning eternity. Death in fact is the door to real life in the Christian worldview, real happiness, real bliss, heaven. But there is no afterlife in the Torah, it’s never mentioned. The focus of Judaism is solely on this world, not on what comes afterward. This world can be heaven, this world can be a place of supreme bounty. And rabbinic Judaism has turned this framework on its head with the idea of Olam Haba, the World To Come. The old sages say that one day, all this you see, it will be gone, and a new, perfect world will stand in its place. A full life of pleasure in this world can’t begin to compare to even a second in Olam Haba. Death is a door to real life, life in the World To Come. Rabbinic Judaism sees this life as nothing more than preparation for Olam Haba, the way Christian’s see this world as testing ground for who gets into heaven. There’s also the idea that the wicked will descend into Gehenna, a place of torment. Sounds a lot like hell.

In my view, this all runs far too parallel with Christianity, and this is why I personally can’t subscribe completely to rabbinic thinking. If I were studying Torah and giving charity to avoid hell, I’d agree with you that I’m engaging in something akin to basic Christian practice. But I don’t think I am.

(Also, going back to Lashon Hara and refraining from evil talk about others: when I say that I try to avoid Lashon Hara since I’m just as guilty as everyone else, I don’t mean guilty of sin, I mean guilty of the same things that we’re inclined to make fun of others for. People are weird, they’re obnoxious, they’re rude, they can be awful. None of these things are sins, but they aren’t exactly nice either. And at times in the past I haven’t been exactly nice, I can be as strange as the strangest of us, so I don’t have much room to speak ill for these reasons, and think the best practice is holding my tongue. No one is born with sin, everyone is born weird.)

Info: Before you go, I wanted to ask a couple selfish questions as a young blogger looking to improve.

First, what tips do you have for being prolific, i.e. writing lots and lots of posts as you’ve been doing?

Second, you conduct maybe the best long-form written interviews I’ve seen on Substack, with some truly brilliant people that bring their A game to the conversation. How do you go about selecting and contacting guests, then preparing questions that draw out such thoughtful and insightful responses?

Sotonye: The only tip I have for writing more is to write when you feel bad. I think a lot of us don’t feel great a lot of the time, whether because of some physical issue or just a sheer lack of motivation, and I think it’s important to understand that 1) there’s a huge opportunity cost to waiting until things are perfect, the biggest one might be the loss of the only form of immortality available to us besides having children: our productivity. When we die only our kids and our work will remain. If we’re idle we lose the chance to maybe have both, so we have to work hard despite everything we feel. 2) It’s important to understand that no one can tell the difference in your work between days where you feel great and days where you feel awful. I’ve written this entire interview feeling completely awful because of lack of sleep, but I don’t think anyone would have been able to tell!

My only other tip would be to find some way to put yourself in a bad situation. A situation wherein, if you don’t write prolifically, you’ll be in serious trouble or face deep embarrassment. My brother always tells me that one of the hardest things in life is having to be your own boss, and he’s right. Being self motivated is a universal problem, no one can figure it out. But the secret is I think just forcing yourself into obligations that will force you to work. The reason I’ve been writing so much recently is because I promised someone I would, the reason why I finished this interview in a day is because I told you I would. Start making promises.

And with respect to my interviews, I’ve actually decided to rethink my entire process and throw most of what I was doing out of the window. I selected guests just on the basis of whether or not they’re interesting and whether or not they have their dms open, but from now on I’m most likely going to interview just one person multiple times. It takes a long time to get responses from the people I contact, and a lot of them don’t reply or they’ll give outstandingly brief answers, and this problem is a massive opportunity cost. I could be writing articles instead of investing in random people, or I could be having a series of conversations with people I know to be brilliant. Which is the idea for my upcoming series with Andreessen Horowitz cofounder Ben Horowitz.

And Ben I think is the answer to your final question. Most of the insightfulness you can pull out during an interview depends on the person you’re interviewing. If I asked Ben a very boring, mediocre question, he could still teach you more about the world than anyone else. Good interviewees make good interviews. I realized this while watching one of Edward Luttwak’s interviews online a while ago. He was being interviewed by one of the worst interviewers I had maybe ever seen, but Luttwak was so interesting that it really didn’t matter. It was honestly amazing and taught me quite a bit about other people. Amazing people are always amazing and you can’t stop them from being that way or cause them to be that way either.

Info: Sotonye, thank you so much for sharing your insights!