Did Sowell Win These Battles?

"Any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats"

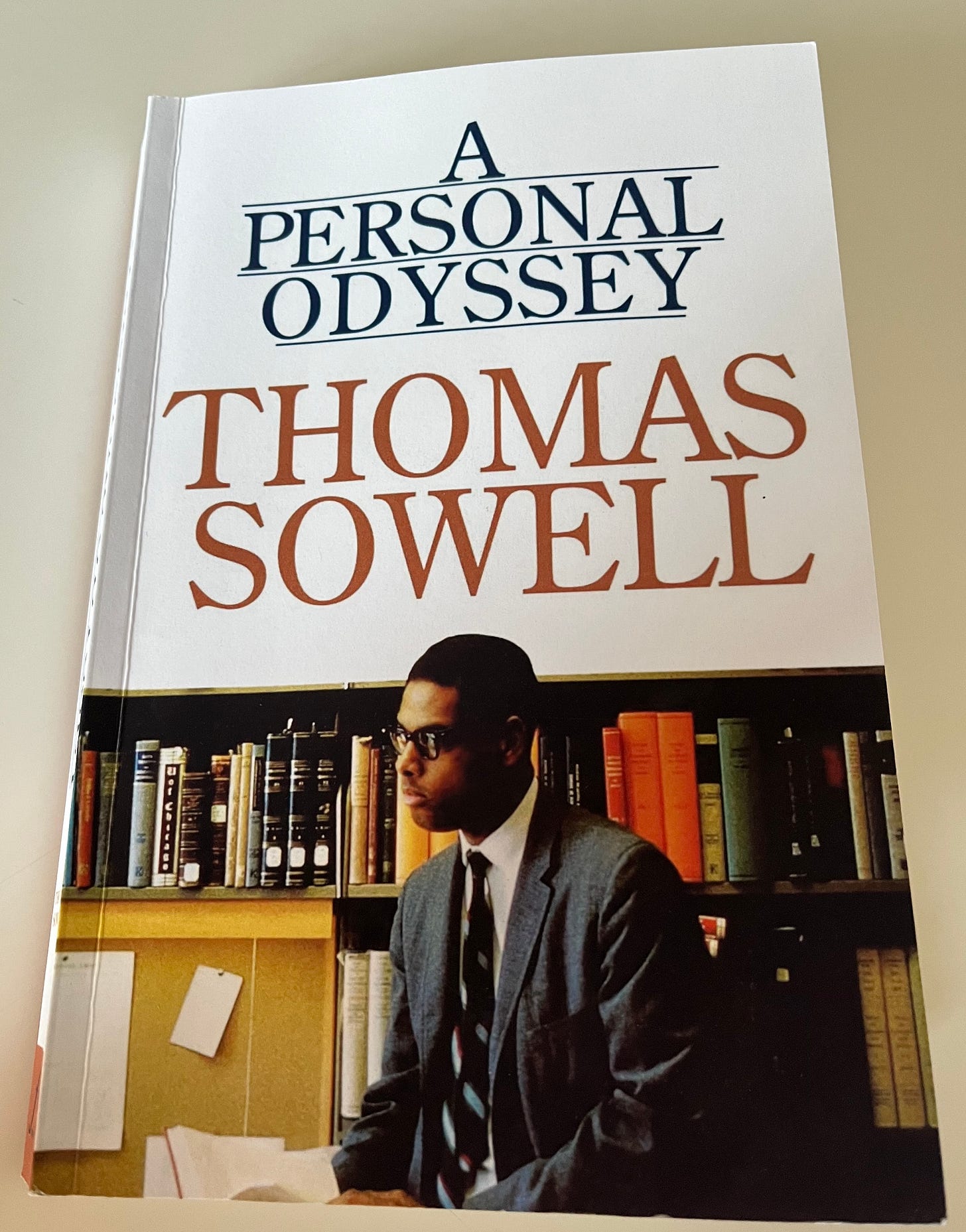

Lately I’ve been reading Thomas Sowell’s memoir, as prompted by

’s stimulating review.Those interested will of course wish to take a look at the excerpts Rob includes from the book, but I was most struck by part of the commentary with which he concludes,

Sowell always comes out with the upper hand in any confrontational interchange. It’s possible that he is just that good. Still, as George Orwell has written, “Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.”

Similarly, the economist and memoirist Glenn Loury has stated, “How does the [memoirist] earn the readers’ trust when the writer is reporting on himself? The only way is by disclosing discrediting information. The writer’s got to put blood on it. You have to say things that are ugly about yourself for the reader to take you seriously.”

Specifically Rob is speaking to Sowell’s social interactions— “with his teachers in school, his superiors in the military, his colleagues in academia, and his bosses, he is invariably the more clever one. It would have been interesting to get a glimpse into the occasions when he was one-down instead of always one-up.”

I’m only just getting into the book, starting from the middle, so don’t take these episodes as a complete or final story on the memoir or the man. But I can’t help from wondering… did Sowell win these battles?

From Thomas Sowell’s “Personal Odyssey”…

All excerpts are chronological, with page numbers from Kindle.

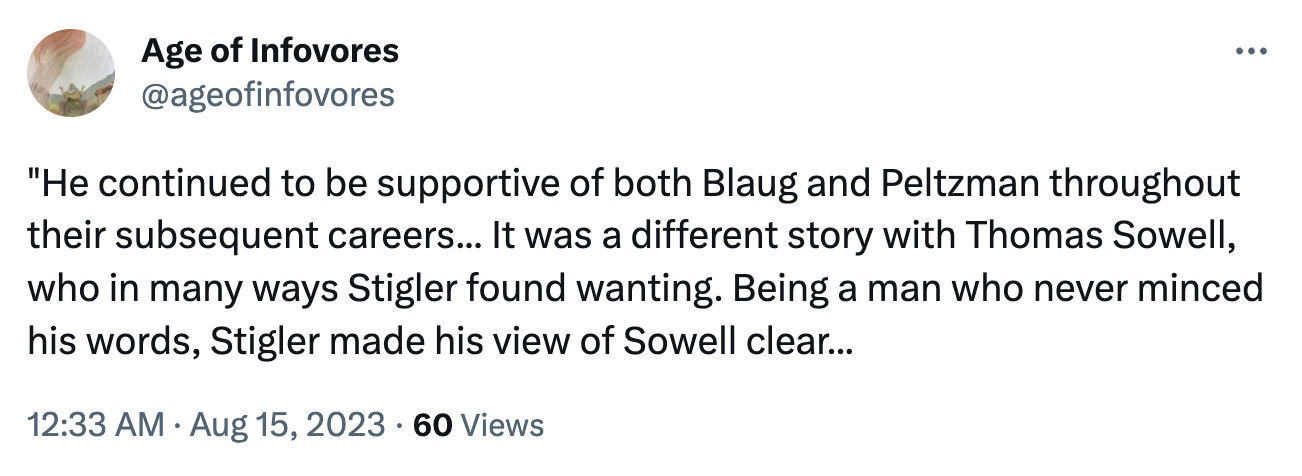

1. Page 138

Before leaving the University of Chicago, I had approached Professor George Stigler with the idea of writing a doctoral dissertation on the history of one of the old standby theories of economics called Say’s Law. Stigler, however, did not think that enough could be said that was new on the subject… [and] in fact considered [my interpretations] to be fundamentally erroneous. Unfortunately, that was exactly my view of his interpretation.

Our lengthy discussions at Chicago were followed by exchanges of lengthy letters after I went to Washington. The best I could get from him was a statement that he was willing to step aside as my thesis advisor in favor of someone else, since “we seldom see eye to eye.”

This was fine in itself, though somewhat ironic in view of my going to Chicago specifically to study under Stigler.1

2. Page 139

One of those interviewing me was a white-maned professor who was about to retire, creating the vacancy for which I was being considered. He was concerned over the fact that I had written on Marx and might be a radical influence on the students.

By this time, there was not a snow ball’s chance in hell that I would be a radical influence, but rather than reassure him on that, I let him know that I thought the question itself was out of line. “My political philosophy is irrelevant,” I said, “because I plan to teach economics and not my political philosophy.”

“But I think it’s relevant in the over-all picture,” the old fellow said.

“Why?” I asked. “I don’t plan to draw demand curves sloping upward rather than downward, regardless of my politics.”

“Well, that’s not the point.”

“Are people brought here to teach economics or to indoctrinate students in their political philosophy?” I asked.

“To teach economics, of course. . .”

After a few exchanges of this sort, I really wrote off the whole thing as a wasted day. But, a week later, they made me an offer and I accepted.

3. Page 149

“Tom,” he said, “the feeling I get from talking to a number of students is that you aim your course at the A and B students—and let the C and D students go to hell. We know the students exaggerate, so I wanted to get the real story from you.”

“No, I think that’s a pretty fair summary of my approach.”

4. Page 160

My tightening up on standards and on cheating initially meant massive failing grades on exams. This in turn meant massive complaints—to me, to the department chairman, and to the dean. One girl who received a very low grade burst into tears and ran into a colleague’s office.

The department chairman only reluctantly discussed anything with me, in view of our very strained relations. (I had called him a son of a bitch to his face, and took off my glasses when I said it.)

5. Page 168

As I wrote to a friend:

“We are just living to get away from this place. It is not only the attraction of returning to the academic world but the repulsion of New York.

There are a lot of cultural attractions here but there is also a lot of wholly pointless rudeness and sick people walking around with chips on their shoulder. One of these started a fight with me in the subway about a month ago. Fortunately, there was nothing bad about him but his intentions. However, I still suffered a swollen hand, a slightly sore shoulder the next day and blood splattered on my clothes.”

6. Page 194

My first run-in with the Cornell administration came when I refused to use the university’s travel agent to arrange the students’ flights to Ithaca. I insisted on using a private travel agent in town, because I knew that I could tell her what I was trying to accomplish, and that she would arrange the travel accordingly.

But the campus bureaucracy, like all bureaucracies, thinks in terms of standard procedures and rules—not results. I could easily imagine Cornell’s travel agent bringing in some students by a roundabout route, with long and tiring layovers between planes, in order to get a fare 10 percent lower.2

7. Page 219

Another unexpected call I received was one from Kenneth Arrow, a world-renowned economist who was president of the American Economic Association, the national organization of economists. He offered me an appointment to the editorial board of the American Economic Review, the Association’s official organ and the most widely read scholarly journal in economics. It was obviously an honor, but I asked: “When was the last time you offered this position to someone who had published nothing during the past two years?”

He was somewhat taken aback by the question, perhaps because not many people look gift horses in the mouth. As I pressed the issue, however, it came out that there was some concern to racially diversify the membership of the American Economic Review’s editorial board. I not only turned down the offer, I told him that such double standards were a terrible and harmful idea. In fact, I was so emphatic that I later phoned him back to say that I was not making an attack on him, but was condemning completely the principle involved.3

It’s getting late, but I’ll close with a few general observations.

Both the superficial and the intimate reveal aspects of individuals that are often important.4 Titles, book covers and footnotes are intentionally chosen, to speak to an audience that shares enough background with the author to take an interest in seeing what he or she sees.

No matter how talented, each person’s vision is constrained.5 It is usually only “by proving contraries” that the truth is perceived.

Be careful what conclusions you draw from smarts, confidence, and aggression6— even outward competence can be misleading without more context to help interpret what you see.7

But those are just some random guy’s thoughts on the (still) passing scene.

See “Intellectual Gladiators” by Bryan Caplan

“I had called him a son of a bitch to his face, and took off my glasses when I said it”

i have been trying to read more biographies of great men

i will add this to my reading list