Seth Stephens-Davidowitz’ new book offers data-driven insights into many of life’s decisions, from finding romantic love to selecting the sport your kids should play.

But of all the compelling topics in “Don’t Trust Your Gut”, one piqued my interest the most—how to find success as a creative person.

II.

Noting that most wealthy people in the United States own some kind of business, the author uses comprehensive IRS tax data to determine the most promising business fields for becoming rich. He uses two criteria:

First, at least 1,500 business owners in this field are in the top 0.1 percent. This means that many people have achieved wealth through this path.

Second, at least 10 percent of businesses in that field had an owner in the top 0.1 percent. This ensures that many of the people who tried this path got wealthy.

Of the many possible fields, only seven clear both hurdles. Here are the top five:

Even with caveats, it turns out that finding success as an independent artist is much more attainable than the one-in-a-million of common parlance tends to suggest. Accounting for selection bias, Stephens-Davidowitz places the true base rate between 1-in-100 and 1-in-200—a long shot for sure, but more in line with your odds of striking rich in a randomly selected vocation.

If these probabilities still seem daunting, you’re in luck—research suggests effective strategies to improve your odds of success substantially.

III.

Determining the optimal approach begins with a firm grasp of the principles that explain artistic success. Stephens-Davidowitz focuses on two:

1. The Mona Lisa Effect

Named after the painting that became surpassingly famous only after becoming the object of a high-profile theft, this principle affirms the crucial role of luck in making it big.

“The Mona Lisa Effect says that unpredictable events massively influence success.”1

2. The Da Vinci Effect

A reference to the Salvator Mundi, a painting whose value dramatically increased after art experts determined it had been created by the man who painted the Mona Lisa.

“The Da Vinci Effect says that the success of an artist begets more success for that artist. People are willing to pay more for the work of an artist who is already famous.”

Sounds pretty arbitrary, but don’t despair—Stephens-Davidowitz assures us there are proactive ways to use this knowledge.

The predominant way that many people deal with these effects is by whining. “Life is so unfair! That work isn’t actually better than mine.” Normally, I am all in favor of whining—and consider it my predominant coping mechanism for adult life.

However, I must admit that the data definitively overrules the justification for whining. Scientists have uncovered patterns of people who tend to succeed as artists, those who have found ways to make the randomness in artistic success work for them.

IV.

The principles in the preceding section are particularly important when quality is hard to assess. Really good measures exist for finding elite basketball players, so scouts routinely find the best prospects even if they come from obscure or faraway places. Evaluating pop music is more subjective, so prospective artists in that field need to do more than simply excel at their craft to be discovered.

What artist behaviors are most likely to invite a breakthrough? Stephens-Davidowitz offers three core lessons:

1. Search far and wide

Many artists handicap their chances for discovery by continually knocking on the same doors and playing to the same crowds. You can do better.

Computational scientist Samuel Fraiberger and his team found that painters who presented in a wide range of galleries were six times more likely to have long and successful careers—usually because presenting in a diverse array of lesser-known venues eventually garnered an invite to more prestigious ones.

Because success in the artistic domain is highly variable and path dependent, the aspiring artist needs to do everything possible to expose themselves to positive tail events with potential to launch obscure but talented individuals into the crucial orbit of career-making connections.

Artists who fail to do this, no matter how gifted, rarely get discovered.

2. Produce a lot of output

Another way to make luck work for you is to send a lot of your work out into the world.

One of the most robust findings in the study of creative achievement is that more prolific creators tend to have the most success. To be sure, the most talented artists often have an easier time producing a lot of work. But part of the reason high-output creators succeed has to do with a simple numbers game.

Consider the example of Pablo Picasso. Out of the 1800 paintings and 12000 drawings he produced over the course of his career, only a minute portion of them were hits. Hundreds of completely unknown works continue to turn up after his death. But while the great mass of Picasso’s outputs provided little direct contribution to his legendary status, each piece incrementally increased the odds that something would take off.

To maximize your chances of outlier success, it’s advantageous to churn out as much as you can.

3. Don’t pre-reject

A corollary to this last point is that even artists routinely fail to assess the quality of their own works beforehand.

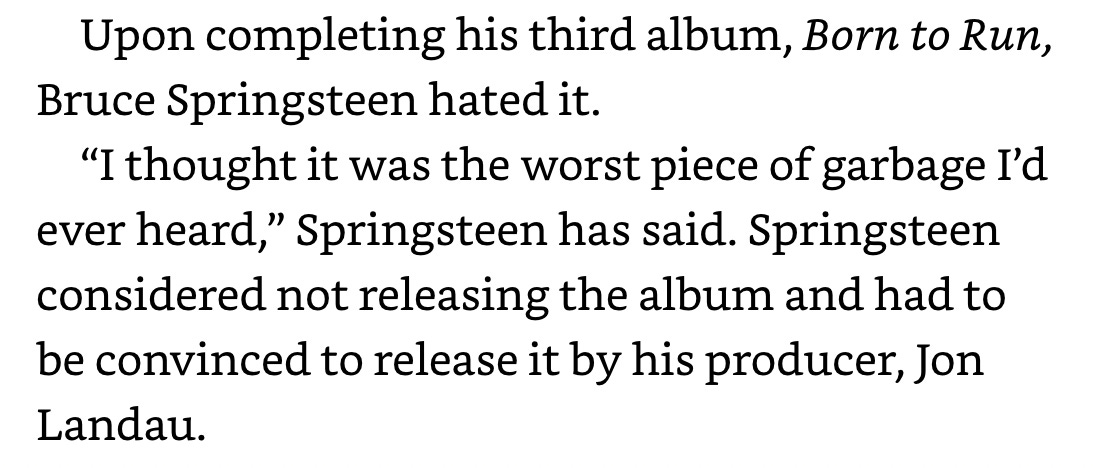

Stephens-Davidowitz points to many examples of artists, from Beethoven to Woody Allen to Springsteen, who reluctantly released works they weren’t proud of only to be met with overwhelming success and critical acclaim in response. What masterworks would the world have missed if these obsessive talents deferred final judgment to their own worst critic?

Trust the process and release your creations into the world. It would be a shame to leave Born to Run forgotten in your file-drawer.2

V.

I would say trying to become an artist is a silly idea if you don’t do the things that I discuss in Chapter 6 that maximize your chances of getting your lucky break. But if you do these things, trying to be an artist may not be a crazy bet, particularly when you are young. Another way to say this: trying to make it big as an independent creative but not producing a ton of work and not hustling to find your break is just about never going to work. (emphasis added)

Prior to reading this book, I approached my writing mostly as a process of trial and error guided by my own instincts. Instincts such as “stick with what you know”, “less is more”, and “be your own worst critic”.

I trusted my gut.

Now thanks to Stephens-Davidowitz, I don’t have to.

Not to be confused with the feeling that a painting’s eyes are following you, also called the Mona Lisa effect.

In case you need further convincing that artistic quality is really, really hard to assess, consider the Weezer album Pinkerton. Rivers Cuomo released this ambitious and personal record with high hopes and was devastated by initially tepid reviews.

He was plagued by self-doubt:

“This has been a tough year. It's not just that the world has said Pinkerton isn't worth a shit, but that the Blue album wasn't either. It was a fluke. It was the ["Buddy Holly"] video. I'm a shitty songwriter."

And radically shifted his own assessment to match the critics:

“It's a hideous record... It was such a hugely painful mistake that happened in front of hundreds of thousands of people and continues to happen on a grander and grander scale and just won't go away. It's like getting really drunk at a party and spilling your guts in front of everyone and feeling incredibly great and cathartic about it, and then waking up the next morning and realizing what a complete fool you made of yourself.”

With time, Pinkerton was re-evaluated as one of the best albums of its era and sold a lot of records. Ten years after its release, Cuomo reverted to his original assessment:

“Pinkerton's great. It's super-deep, brave, and authentic. Listening to it, I can tell that I was really going for it when I wrote and recorded a lot of those songs.”

But what about the first four things on the list? (and where do professional athletes rank?)

I may be misunderstanding something in the beginning but I feel like there is a great deal of silent data that is being ignored in this analysis. I think what we're really saying is that, of the successful artists, the top establishments are a relatively larger group than other industries. But I could be misunderstanding.

It's always interesting to me to mix the world of innovation with the world of cause and effect. The nature of artistic creative expression is most successful when it is new--describing a mechanistic formula promising artistic success is somewhat ironic.

Still it's certainly true that those who have are given more. While those who have not lose even that which they have.

Obviously this was a good article as it sparks lots of thoughts!