I am going to suggest that the Golden Age is here. It’s just not evenly distributed.

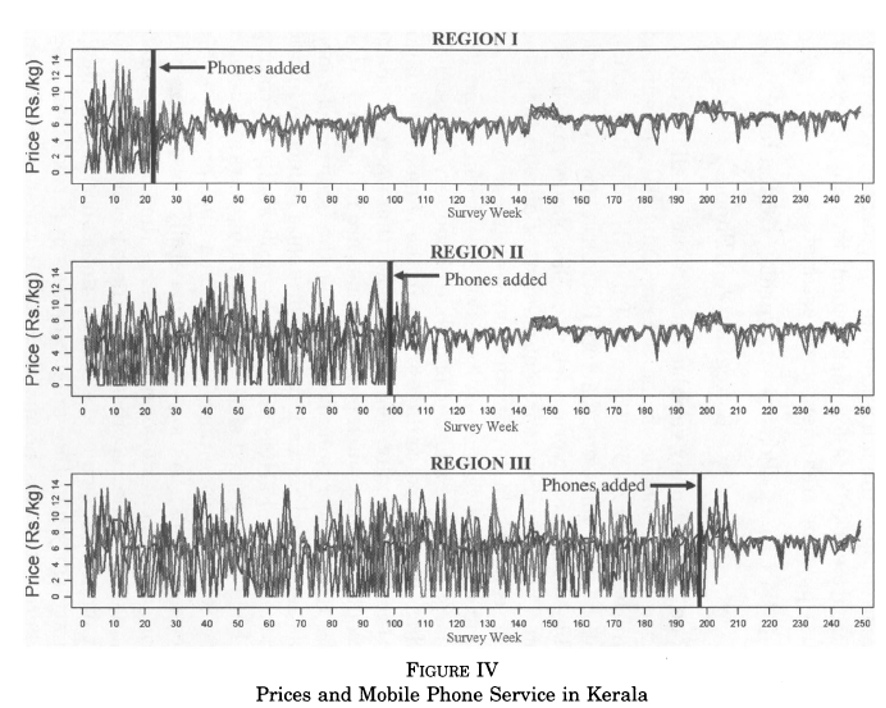

On January 1, 1997 mobile phone technology was introduced in Kerala, a small state on India’s southwestern coast. In previous years, local fishermen took their daily haul of sardines to the nearest beach market and sold the fish at auction without any guarantee of finding a favorable price. But as mobile phones gradually spread to each region, fishers gained the ability to contact potential customers in many different markets before coming to shore. As a result, profits increased, prices became less volatile, and waste was reduced from 5-8% of daily catch to essentially zero. In the words of the paper’s author, Robert Jensen, “the fisheries sector was transformed from a collection of essentially autarkic fishing markets to a state of nearly perfect spatial arbitrage.”

In this instance, cheap and abundant information not only ushered in a golden age of sardine fishing but also distributed it fairly evenly. Regions still differed to an extent in terms of access and economic development, but as mobile phone towers were built in each successive area, adoption quickly attained a critical mass sufficient to improve market functioning for most participants.1

If this were always the pattern we observed as technology advanced, we would have great cause for optimism. Indeed, we still do. But before I indulge in the optimism of this moment, I will first present three important distributional caveats to our information golden age.

Attention, Please!

I can look down on my phone and see the most interesting thoughts from the most interesting people on the most interesting topics. Twitter is an ongoing global tournament to rank people by interestingness as determined by likes and follower counts and machine learning algorithms. Who’s more interesting: the person who happens to be sitting next to you in real life or the most interesting person in the world talking about your favorite topic? No wonder everyone is staring at their phone.

The matching technologies I discussed in my previous reflections enable individuals to find what they want much more quickly and efficiently than before. Amazon finds what I want to buy. YouTube finds what I want to watch. Facebook finds who I want to friend. This is largely a positive development—so long as what I’m searching for can be specified up front, technology helps me find it with minimal cost.

These developments probably even benefit the less fortunate more than the well off in some ways. If I don’t have much money, finding the right thing to buy at the right price is especially important and cheap access to entertainment and instruction is a godsend. If I feel lonely or disconnected from my local community, social networks can help me find people I relate to.

But in other, deeper ways this hyper-matching environment is profoundly unequal. The “global tournament for interestingness” carried out by online platforms is great at identifying winners that excite, provoke, titillate, and entertain us but crowds out more local relationships that have traditionally provided a space for love and affection removed from market competition. In the process of directing increasingly large shares of our attention to a small number of very famous people, less is left for the relatively ordinary and unpopular.

When Noise Beats Signal

While the printing press paid almost immediate dividends in the production of higher quality maps, the bestseller list came to be dominated by heretical religious texts and pseudoscientific ones. Errors could now be mass-produced, like the so-called Wicked Bible, which committed the most unfortunate typo in history to the page: thou shalt commit adultery.

Nate Silver, The Signal and the Noise

Sometimes achieving an even distribution creates its own problems, by allowing information of dubious quality to drown out more reliable signal. This is the lesson of Borges’ Library of Babel, where a library containing every true book is spoiled by the catch that it contains every false book as well.

We can relate this idea to the attention economy of the previous section by invoking Gresham’s law—because social media platforms assign equal value to likes, follows, and shares of high and low quality alike, we can expect to see the bad drive out the good with some regularity. Sometimes this takes the form of literal abstention, as thoughtful and polite users bow out, but is most evident in existing users conforming to the lowered standards of the platform.

For a historical illustration of the downsides of democratization, consider this excerpt from Stephen Budiansky’s Journey to the Edge of Reason which relates a turning point in the liberalization of 19th century Austria.

The English-style Liberal party that had dominated Austrian politics for the first decades following the 1867 constitution had advanced economic liberalism and expanding democracy—both of which now unleashed forces that turned against them. Only 6 percent of Austrians had the right to vote in the 1860s. But the subsequent expansion of the franchise empowered populist and nationalist movements whose competing demands could not be met.

The Reichsrat dissolved into noisy brawls in which competing parties flouted the rules of procedure, staged marathon filibusters, and smuggled in cowbells, harmonicas, whistles, and drums to drown out members of the opposing parties when they tried to speak.

“The advent of brutality into politics chalked up its first success,” Stefan Zweig wrote of those events in the 1890s. “When the underlying rifts between races and classes, mended so laboriously during the age of conciliation, broke open they widened into ravines” (emphasis added)

Paradoxes of Equality

In each country and region, more boys than girls aspired to a things-oriented or STEM occupation and more girls than boys to a people-oriented occupation. These sex differences were larger in countries with a higher level of women’s empowerment.

Sex Differences in Adolescents’ Occupational Aspirations (Stoet and Geary 2021)

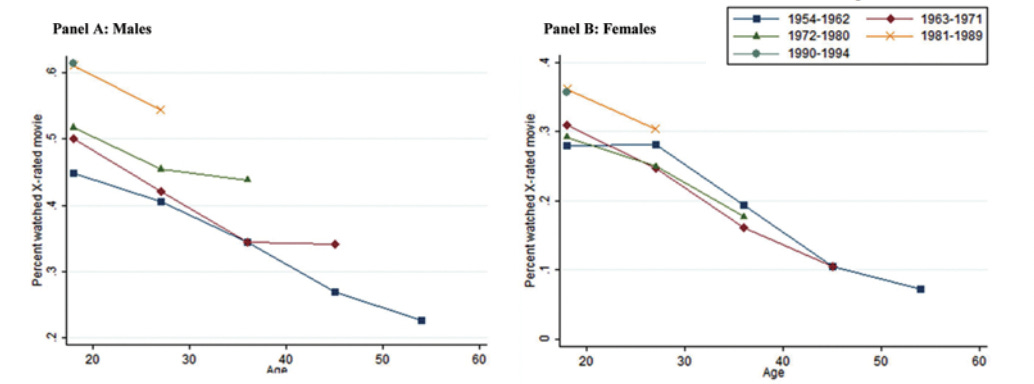

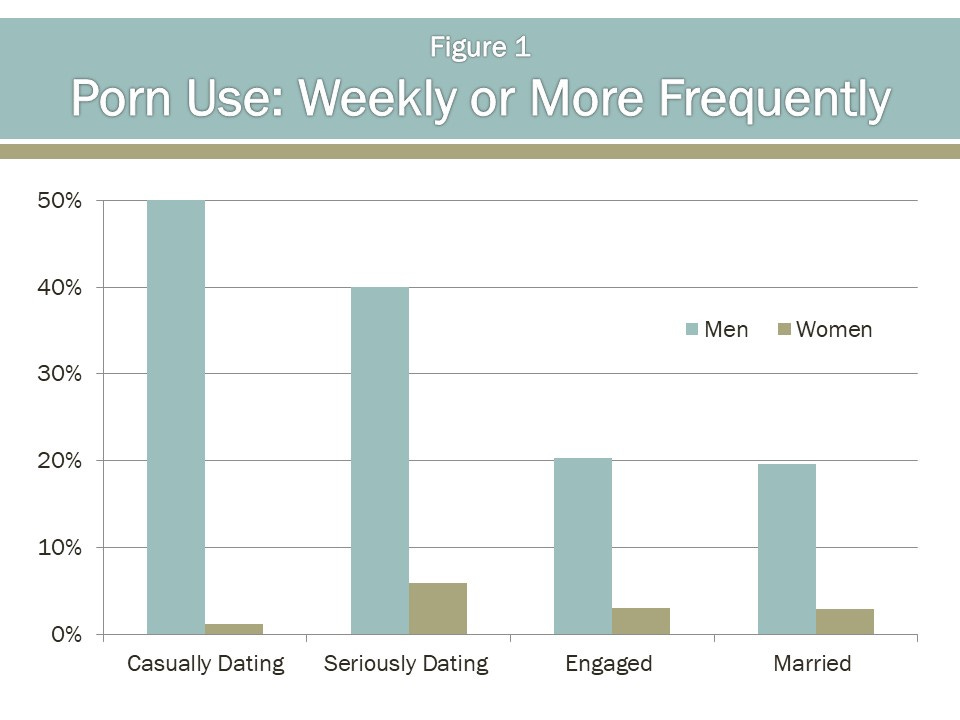

As in the controversial gender-equality paradox, a more even distribution of choices can result in a less even distribution of outcomes. Consider the example of pornography, which is used disproportionately by men despite being readily available to anyone with an internet connection:

Even more striking than the current size of the porn gap is how it has widened over time. Comparing 18-26 year old individuals of both genders from the 1972-1980 cohort (green) to the 1981-1990 cohort (yellow) reveals a much larger jump in usage among men. This latter cohort included the first people to experience the internet as adolescents, and is thus consistent with the theory that broad expansion in choice allows increasingly uneven outcomes to manifest.

This phenomenon applies more generally and often in the physical world as well as online. As food options have proliferated and exercise has become more optional, the gap between the Americans with the highest and lowest BMIs has widened dramatically. It is fashionable to argue that these gaps are caused by “food desert” communities with limited incomes and access to healthy options, but the best studies suggest that this is fundamentally a phenomenon of choice. Anywhere we see broad expansion in the available choices, we can expect greater dispersion in the outcomes we observe.2

Substack Revolution?

So what do I make of our purported golden age? Like Arnold, I can attest to the flowering of intellectual output disproportionately represented on Substack—l have more to learn from Scott Alexander, Matt Yglesias, and Bari Weiss than I have time for them to teach me. Same goes for Yascha Mounk, Glenn Loury, and Freddie deBoer. I could go on.

And yet as many as there are, I’m confident there will be many more important arrivals to the scene. Richard Hanania had only written one major article prior to our second Fantasy Intellectual Teams draft back in May and was considered a risky pick. He’s since become a star contributor in a moment we’ve ventured to compare with Ancient Athens or the Scottish Enlightenment.

A vision this grand is worth pursuing almost regardless of whether it even succeeds or fails. No matter how it is distributed, I want to be a part of it.

“While it was primarily the largest fishermen who adopted mobile phones in the present case, there were significant spillover gains for the smaller fishermen who did not use phones, due to the improved functioning of markets. Thus, rather than simply excluding the poor or less educated, the “digital provide” appears to be shared more widely throughout society.” While distribution is even in the sense that nearly everyone benefits, it is likely that some benefited much more than others—a phenomenon I touch on in subsequent examples.

This is even true of mobile phone adoption among Kerala fisherman. “Boats with mobile phones gained more (nearly twice as much) in part because they are, on average, larger boats and thus catch more fish and because they are more likely to be able to profitably exploit the small remaining arbitrage opportunities. . . . However, phone users had a clear positive externality on nonusers, who will, for example, no longer have days with unsold fish because boats with phones will switch to other markets when the local catch is high.” One way to think about Golden Age distribution is in terms of externalities. When adoption has large positive externalities, as in the case of sardine fishing, we may welcome greater inequality in return for welfare gains. If we think in terms of avoiding the worst outcomes (e.g. starvation, high volatility) we might even view these outcomes as a sort of reduction in inequality. When externalities are negative, inequality promoting technologies may be cause for alarm.

Another great article. It's interesting to see widening gaps as globalization opens up information markets to previous non consumers. I've thought a lot about the library of babel story you've mentioned a few times. It seems that the real question in our world of infinite information is how to discern truth over error and which truths are of most value.

Regarding the paradox of porn equality, aren't porn supposed to lower sex drive in men but increase sex drive in women? Which in turn is used as a psychic cage for already unwanted men and a marital aid for women? https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100516X

This becomes a libertarian but anti-egalitarian argument, as "equality of sexual opportunity, not equality of sexual outcome". Incel proletarianism sounded less like a parody and more like moral misguidedness of factual reality. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7xPMYeb80bo