More than 700 years after publication of The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri’s descent through the nine circles of Hell maintains a remarkable hold on our imaginations. Market research in advance of Dante's Inferno the videogame showed that 83% of those surveyed had heard of the book and nearly a fifth could explain its contents. The release went on to sell half a million copies in its first month.

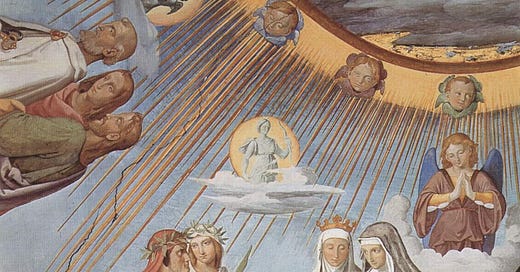

Dante’s Paradiso in contrast, depicts the poet’s ascent into heaven—and is largely ignored. This is not the only setting in which Hell seems to have the upper hand.

In The Churching of America, sociologists Roger Finke and Rodney Stark argue that the United States was once much less religious than it is now. In 1776, only 17% of Americans belonged to a church and observance generally resembled that of Europe before undergoing a steady rise over the following centuries. What explains this religious divergence? In a word, Hell.

While European nations have maintained a central role in promoting establishment churches with subsidies and official recognition, the American Revolution established a country that privileged no religious creed over another. This allowed new religious sects to emerge in competition with mainline churches, and many of these revivalist congregations embraced the rhetorical power of Hell.

Once competition began in the eighteenth century, the greatest surge in devotion occurred not in mainline churches but in new Methodist churches continuing the hellfire tradition of Whitefield and Edwards. The Methodist preachers, far from being products of divinity school, were often local residents, unpaid amateurs supervised by visiting circuit riders who themselves lacked seminary training. From a tiny sect in the 1700s, the Methodists grew by 1850 into America’s largest religious denomination.

Whatever your opinion of these religious developments, it seems fruitful to consider why Hell is so captivating while Heaven loses our interest. In the process I hope to shed light, if only indirectly, on a central reason why so many of our institutions seem to fall short of the ideals we claim to espouse.

Our Utopian Hypocrisy

When we talk about an ideal world, we are quick to talk in terms of the usual things that we would say are good for a society overall. Such as peace, prosperity, longevity, fraternity, justice, comfort, security, pleasure, etc. A place where everyone has the rank and privileges that they deserve. We say that we want such a society, and that we would be willing to work and sacrifice to create or maintain it.

But our allegiance to such a utopia is paper thin, and is primarily to a utopia described in very abstract terms. Our abstract thoughts about utopia generate very little emotional energy in us, and our minds quickly turn to other topics. In addition, as soon as someone tries to describe a heaven or utopia in vivid concrete terms, we tend to be put off or repelled. Even if such a description satisfies our various abstract good-society features, we find reasons to complain. No, that isn’t our utopia, we say. Even if we are sure to go to heaven if we die, we don’t want to die.

Robin Hanson explains many phenomena of human behavior by highlighting our innate desire for social status. We don’t want to be rich, powerful, or successful for their own sake as much as we want to be MORE rich, MORE powerful, and MORE successful than the person next to us. We are essentially competitive in nature, driven to excel even at the cost of conflict.

Given this thesis, it’s unsurprising that Dante’s Paradise would inspire less interest than his competing vision of Hell. Consider a well-known passage in which Dante asks Piccarda whether she aspires to a higher position in Heaven, with a more breathtaking view of the cosmos and more friends to consort with.

Brother, the power of love subdues our will

so that we long for only what we have

and thirst for nothing else.

If we desired to be more exalted,

our desires would be discordant

with His will, which assigns us to this place.

Piccarda’s satisfaction with her station stands in stark contrast to the inhabitants of Hell, whom Dante describes as “envious of every other fate.” Heaven is peaceful, serene, and uncompetitive and these defining traits establish Paradiso as antithetical to the Hell we find so compelling.

The bulk of Piccarda's answer to Dante's question begins with the word frate (brother), the word that was nearly absent from Hell. . . [This form of address] insists on the relationship that binds all saved Christians in their fellowship in God, a sense that overcomes the inevitable hierarchical distinctions found among them in this life. The love that governs their will is nothing less than charity, with the result that it is impossible for them to want an advantage over their brothers and sisters in grace. To wish things other than they are, to desire one's own “advancement,” is nothing less than to oppose the will of God. And thus all members of this community observe the gradations among themselves, but find in them the expression of their general and personal happiness.

Our revealed preference for Inferno suggests our true desires for brotherhood and tranquility fall short of what we profess them to be. If thirst for higher status drives our interactions, reducing conflict only serves to limit opportunities for advancement.

High School Hellscape

Does anyone else find it weird that 90% of movies and shows about high school portray it as this utterly cruel site of unrelenting social competition where rigid cliques exist on a transparent popularity hierarchy, a hierarchy which determines whether individuals within it experience school as a place of privilege and prestige or of loneliness and misery? Where the starting quarterback dates the head cheerleader and they go on to be the prom king and queen? Where sensitive and quirky types are universally ignored, if lucky, and bullied if not? Where every student is sorted into one and only one clique, never multiple at once, largely because those cliques are determined by everyone having one overarching style or interest or archetype? Seriously, those tropes are found in so so much of high school media, this one particular read on what it’s like, a conformity of portrayal that’s hard to find in any other genre. And I don’t get it!

Freddie deBoer, Perhaps High School is Not Always a Relentlessly Brutal Nietzschean Hellscape

The absurd levels of conflict present in High School movies are consistent with Hanson’s view of conflict as prerequisite for status advancement, particularly considering that the status motive is strongest among the young.

Picture a High School resembling Dante’s version of Heaven, where any hierarchy that exists reflects a perfectly just assessment of personal character. The most popular kids are also the nicest and legitimately display many admirable qualities. Even if you desire greater popularity for yourself, it might be difficult to justify displacing someone else in this environment.

Indeed real-life is often like this, as deBoer observes,

Popular people usually (though far from always!) are popular because they’re friendly and kind. The most popular person in my graduating class, bar none - crushed every student council vote, ran unopposed as class president, was welcomed by everyone - was not the head cheerleader or voted most attractive or a queen bee sitting on top of a gaggle of lieutenant bees. She was just an exceptionally good person, someone who went out of her way to include everyone and who was accepting of others without fail.

While this sentiment may be uncongenial to some, it accords with a lot of my experience. Some of the friendliest people I met in High School were also among the most popular and in years since I have often been surprised to discover that unexceptional acquaintances in terms of looks or athleticism were class presidents or prom queens.1 Because painful experiences tend to stick in our minds and kind people are less likely to boast about achievements, this may even be more common than my memory acknowledges.

Yet as comparatively just and pleasant as the low conflict high school experience of the real world is, it fails to satisfy our desire for status. In the movies, schools run by “Mean Girls” and bullies who prey on the weak provide justification for dramatic reversals of fortune and vicarious wish fulfillment as the less popular main character viewers identify with rises in rank. That we find this fantasy compelling suggests our natures may be more prone to justify conflict than we like to let on.

How Institutions Hold Hell at Bay

Another way to approach deBoer’s question is by asking its opposite. If humans are prone to justify conflict in their lust for status, why doesn’t real life more closely resemble the relentless infighting and social competition of a High School movie?

At the start of this series on Institutional Rationality I wrote,

A rational institution orients individuals toward productive ends and facilitates the cooperation necessary to achieve those ends. . . In order to successfully structure our collaboration toward productive achievement, institutions must constrain our choices and behavior.

Institutions establish formal roles and expectations for individuals that reward cooperation while discouraging counterproductive behavior. They make it hard to justify conflict by promoting norms of civility, deliberation, and identification with a greater whole. As a result, high-status individuals in the context of civilized society have been able to achieve prominence primarily through cooperation and pro-social behavior rather than zero-sum competition.

Today many of these norms are being threatened by technological change that upsets the functioning of our institutions and leads much of society to lose sense of any common reality. Contentious social media platforms (sometimes called “hellsites”) subvert rational discourse and intimidate the innocent while insecure insecure elites increasingly consolidate into a monoculture incapable of sound judgment or principled leadership.

Given these challenges, it is tempting to dispose with the old hierarchy entirely through radical decentralization. By devolving more power to individuals via distributed ownership on the blockchain, social networks and intellectual property could conceivably be managed democratically

While I make no claim about the technical feasibility of Web 3.0, I am doubtful we can innovate our way out of institutional decline in this manner. Too much democratization has its own attendant pitfalls, and tokenizing a vast web of social interactions into what is essentially a monetary transaction leads even me to worry about commodification.2

Instead of looking to Crypto billionaires and Angel investors for salvation, we can each play a part in rediscovering the central role of institutions in turning us away from the hellish aspects of our nature and perhaps inch our society a little closer towards a more positive future. Some of our most pivotal institutions are local and within our power to directly affect. There’s no better day to begin.

In high schools across the country it is even remarkably common for friendly or sympathetic disabled students to be elected as Prom Royalty, though the merits of this practice are debatable. My Senior Prom King was a gregarious boy with a significant learning disability who channeled his incredibly high energy into a starring role as our school’s football mascot.

In Why isn’t Capitalism more Caring, I referenced an insight from Hayek’s The Fatal Conceit: just as it is misguided to apply collectivist intuitions evolved in a tribal setting to society at the macro-level, applying impersonal market practices to intimate relationships with family and close friends “would crush them.”

Fun read but I do feel this was a missed opportunity to take a knock on christian rock. But I enjoyed it none the less.