Let knowledge grow from more to more,

But more of reverence in us dwell;

That mind and soul, according well,

May make one music as before

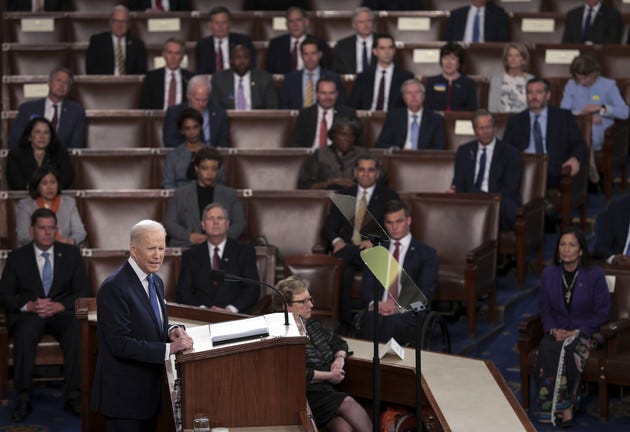

Masks are coming off across the country, even in many places that have been almost militantly in favor of them. At the recent State of the Union address, only a handful of Democratic congress members were masked.

Memory slips away from us with time, and our conception of what we felt and experienced during the pandemic will gradually shift and be remade according to how future events play out. Before that happens, I offer three reflections on what I learned from masking.

1. Lookism is real

Prior to the pandemic, I was skeptical of Tyler Cowen’s claims about looks-based discrimination. No longer.

Moving to a new place last year where the vast majority of people I met were initially masked shattered all of my illusions that disparities in attractiveness might simply be the result of hard-to-measure confounding variables. When someone went from masked to unmasked for the first time, I could observe signs of lookism in my own feelings directly.

What I noticed most often was a sort of Halo effect in which I tended to assume the people I met and liked were more attractive than they actually were. If a colleague was highly competent, professional, and personable I assumed he/she also had nice teeth and bone structure that complemented what I could see. On one particular occasion, I was actually surprised to discover a coworker had pleasant facial features and it dawned on me that my overall impression of him was quite negative. In lieu of strong feelings either way, I tended to give people the benefit of the doubt in my looks assumptions, perhaps due to base rates (on average my colleagues are accomplished people) or the relative pleasantness of holding an attractive mental image of the person.

To steel-man my no longer held view minimizing looks-based biases, it is probably the case that below-the-mask facial features provide some genuine information about what people are like. Someone who attends more carefully to their dental hygiene is likely more orderly and attentive in other areas for example, and incorporating that reasoning into our judgments is not entirely unjustified, or even necessarily negative.

But this can’t be the whole story. Given my apparent tendency to extrapolate excessively from character traits to facial appearance, I’m confident I do the reverse. If subtle confounding variables explained everything, I would expect unmasking to prompt a negligible update to my perception of a person after already becoming well acquainted with them, but I found that this was generally not the case. That many of those I observed in this way dressed well and maintained an attractive overall appearance further undercuts this explanation by leaving less substantive non-looks information to be explained by appearance under the mask.

I now believe that lookism is real, significant, and largely unconscious.

2. Non-verbal cues matter a lot

Trying to get to know people in exclusively masked settings was remarkably unrewarding—even after multiple friendly interactions with someone, I seldom felt that I truly knew the person. Perhaps more importantly, it was hard to feel that they knew and approved of me, and that inhibited my ability to relax and let my guard down.

Much of this difficulty stems from the absence of rich non-verbal cues in masked communication that help conversation partners perceive nuance in what is being said and detect how well their words are being received. These cues also provide much of the payoff to our efforts to be social—it is much more pleasant to be met with a warm smile than a blue square of thermoplastic polymer.

While masking probably did serve a necessary function, particularly prior to the vaccine coming available, it is simply not the case that going without unmasked face-to-face contact indefinitely is “not a big deal”.

3. Small frictions matter a lot

More broadly, masking taught me how impactful small frictions of almost any kind can be. The slight reduction in audibility masks imposed made me more inclined to remain silent and this effect was amplified by everyone else being less likely to initiate conversation as well.

On other occasions masks exerted their influence indirectly, as I chose to preemptively avoid situations that might require them. Even without any social element to the activity (e.g. visiting the library), the small discomfort of a mask was often enough to change my decisions substantially.

Conclusion

As I reflect on the profound impact masking has had on social life over the past two years, I can’t help but wonder how our national unmasking may prove to be more transformative than we expect. What features of our masked world are likely to carry over into the future and which will fade?

While I don’t envision a world restored to what it was pre-pandemic, I do believe significant reversion to the mean is likely along several dimensions. Work from home arrangements will remain more desired and attainable than they were prior to Covid-19, but more than the surveyed 10% of employees will ultimately wish to return to a maskless office. Elevated crime rates are also likely to stick, but the spike in public robberies and assaults may prove less enduring as masks become abnormal.

And our partial reprieve from the exacting demands of beauty? Well, nothing lasts forever.

The importance of facial expressions and nonverbal body language really stuck out to me during this experience, too. I never anticipated how profoundly I would miss the experience of exchanging polite smiles with strangers.

Charles Darwin wrote, “The power of communication … has been of paramount importance in the development of man; and the force of language is much aided by the expressive movements of the face … We perceive this at once when we converse on an important subject with any person whose face is concealed.” The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals" (1872)