Having Eyes to See

Thoughts on why education is so difficult

No man can reveal to you aught but that which already lies half asleep in the dawning of your knowledge. . .

If he is indeed wise he does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind.

When we don’t understand an idea or perspective, our tendency is usually to attribute failing to the person giving the explanation. While demanding a high level of clarity from speakers yields benefits in many domains, this expectation itself is contextual and may not be appropriate everywhere.

For this reason, it may be useful to consider persistent misunderstanding in light of the fundamental challenges that make teaching in any form a difficult endeavor. I will present three.

People are unwilling to learn

When dealing with people, let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic. We are dealing with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudices and motivated by pride and vanity.

Dale Carnegie, How to Win Friends and Influence People

People are often simply unwilling to learn the things that others wish to teach them. Sheer disinterest may be just as common a culprit as stubbornness or pride, as evidenced by the fact that High School students so frequently list boredom as a major reason for dropping out. To have any hope of reaching such students, a teacher must take these sad realities into account.1

Dale Carnegie succeeded at writing one of the most sold books of all time in part because he understood this. Among his maxims in How to Win Friends and Influence People are:

Talk in terms of the other person's interest

The only way to get the best of an argument is to avoid it

Show respect for the other person's opinions. Never say "You're wrong."

Let the other person feel the idea is his or hers

Try honestly to see things from the other person's point of view

Call attention to people's mistakes indirectly

Make the other person happy about doing what you suggest

Note that this is not just good advice for becoming a big success in business, but for becoming an effective teacher. And as an effective teacher himself, Carnegie applies these maxims by framing his lessons in a way that appeals to what most readers are interested in—popularity and power. But is Carnegie merely an apostle of enlightened self-interest?

By offering to teach readers how to win friends and influence people, Carnegie gives people what they want in a way that furthers his higher purpose—teaching readers to be genuinely decent human beings.2 “How to be Kind and Thoughtful to Everyone You Meet” just doesn’t sell as well, particularly not to those who most need the message.

People are often ignorant of how (or what) to learn

So much of education is teaching people context. That is why it is hard, and also why it often does not seem like real learning.

Bryan Caplan makes a compelling case against education, largely on the basis that measured learning retention is low and mismatch between what students study and eventually do in the working world is high. If we accept his figures and interpretation, virtually the entire education system is a colossal waste of time and money.

But before we dismiss the returns to schooling entirely, consider what could be called Bryan’s case for education:

When I’m going through and reading papers, oftentimes I’ll find that there’s something I don’t understand very well or something that seems questionable. Usually, as long as the authors are living, I do try to actually reach out to them. . .

I’m always worried about this autodidact’s curse, where you’ve read a ton of stuff but you still haven’t actually talked to anyone who knows what’s going on. This is one of the things that I try to do to deal with especially the wisdom of a field. Oftentimes there’s wisdom in a field, where it’s known to people who have thought about it for a long time, but they don’t write it down.

Here Bryan is making a case for the importance of context in knowing where to look and how to frame existing insight in its proper light. His work itself is an admirable achievement in learning from others with vastly different knowledge and experiences.

But while this process is second nature to Bryan, most people start out with very little intuitive understanding about how or what to learn. At an embarrassingly basic level, they need to start by recognizing that there are diverse kinds of knowledge and experience to learn from in the first place.

And for a lot of people that recognition has come from formal education.

If I hadn’t been sent to the Mitchell Library as a schoolboy, I wouldn’t have understood that history was this unmanageable quantity of data. I remember seeing the shelf of books about the Thirty Years’ War. I’d been asked to write an essay on the Thirty Years’ War. I went to the Mitchell Library, and there were all the books on the Thirty Years’ War. And it hit me, “Oh my God, there are just hundreds of them.”

That was when the challenge of history suddenly gripped me, that there was this vast, almost unmanageable body of literature to read on any topic.

Even highly intelligent, educated, and curious people struggle when confronted with alien subject matter

Ever wonder about the vast universe of critically acclaimed aesthetic masterworks, most of which you do not really fathom? If you dismiss them, and mistrust the critics, odds are that you are wrong and they are right. You do not have the context to appreciate those works. That is fine, but no reason to dismiss that which you do not understand. The better you understand context, the more likely you will see how easily you can be missing out on it.

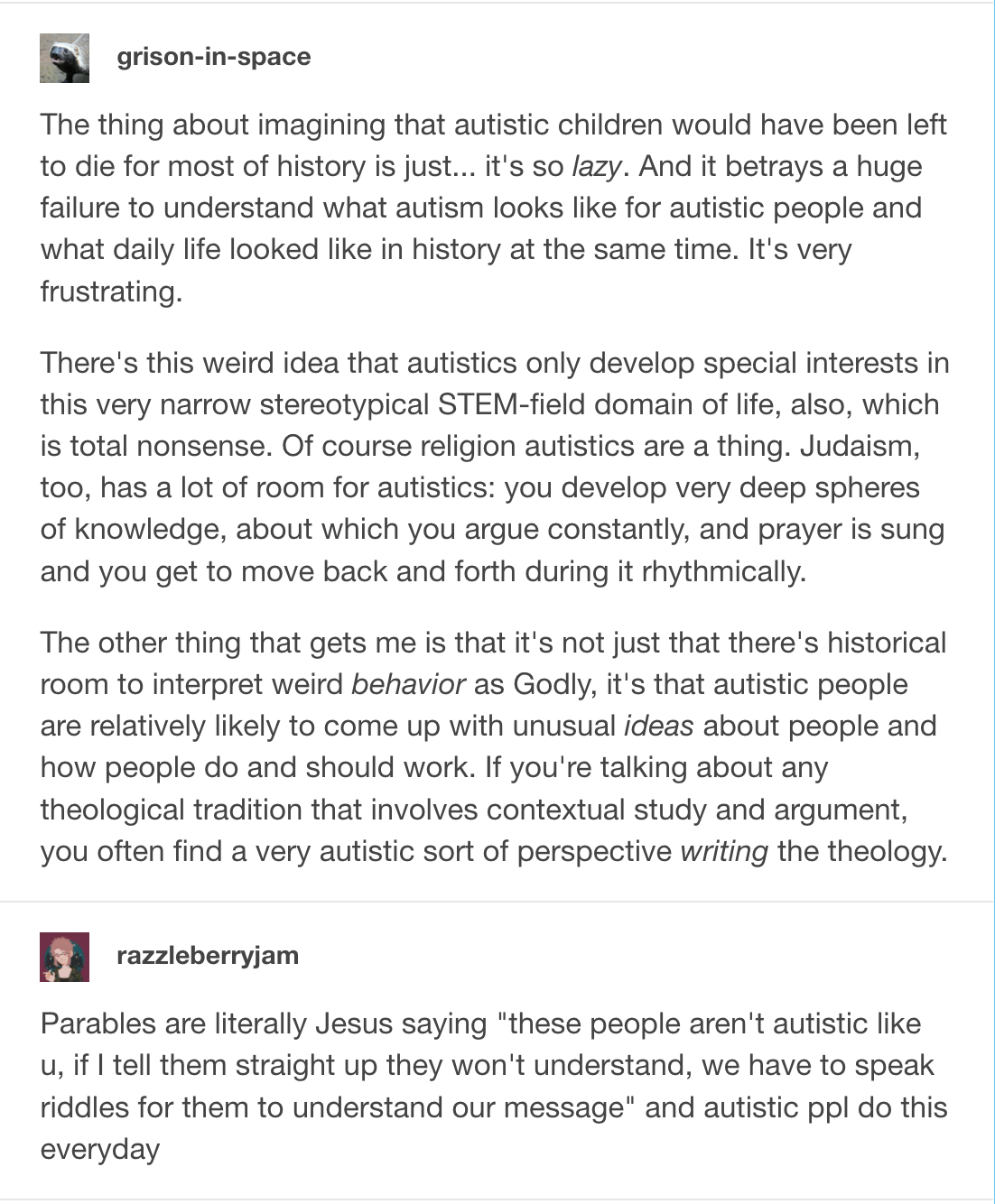

It is challenging to teach someone to appreciate things that are foreign to their personal experience. To illustrate, consider a recent Tumblr thread I came across on the topic of religion and neurodivergence:

How would I begin to explain to the general reader how to go about engaging with the ideas presented here? Apart from the the obvious advice to read the whole thread, I’m really not sure. Reading The Age of the Infovore would help, and I think razzleberryjam’s comment is interesting in context of my last essay, but even that background may not be enough to fully appreciate what is going on here.

The point is not to insist that each one of you drop everything and studiously apply yourself to understanding the context behind what these anonymous microbloggers are talking about. Time too is scarce and should be applied to understanding what will be of most worth to you. But we can use this example to suggest a few principles for recognizing when there is more to something we may be inclined to dismiss.

Note that the posters here all seem to know exactly what the others are talking about. This is a sign that despite the bizarre confluence of topics (religion, neurodivergence, cultural and historical attitudes), there is something real there.

Not only do these posters seem to know something about the various topics—they clearly matter very deeply to them. When reasonably thoughtful and intelligent people take the time to think seriously about a topic and organize their thoughts, that too is a good indication that they may be onto something worthwhile.

There are often clues about a person’s identity and experience that suggest they are uniquely likely to have specific kinds of insight. In this case, the hosting profile says “an autism trapped in a person body” and we might also infer that other participants in the thread have personal experience with direct bearing on this discussion.

Having Eyes to See

And in them is fulfilled the prophecy of Esaias, which saith, By hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand; and seeing ye shall see, and shall not perceive. . .

But blessed are your eyes, for they see: and your ears, for they hear.

While there is much wise teachers can do to facilitate understanding, wisdom itself teaches the need for perceptiveness on the part of the learner. To make the most of a world of limitless and conflicting information, we must develop our own capacity to clearly discern truth from error.

In the words of Bryan Caplan, “a teacher is an entertainer or he is a failure.”

Take a look at some of Carnegie’s other maxims:

Don't criticize, condemn, or complain.

Give honest and sincere appreciation

Become genuinely interested in other people

Smile

Be a good listener

Make the other person feel important – and do it sincerely