Seeing the world as it is

Is polarization underrated? A conversation with Cactus Chu

Substacker Brian Chau writes From the New World, a newsletter devoted to political theory, in particular the inner workings of institutions. He doesn’t care much for personal biography, so we’ll jump right into the ideas.

Info: The about section of your newsletter summarizes your political philosophy as “see the world as it is, not as you wish it to be”, with everything else as application. Given that, I’ll name a few things and you briefly tell me how that thing is different from what we tend to wish it was.

Brian: Answering this part of the question is quite difficult because different people have different ideas of what they wish the world to be. I’ll mostly be targeting these answers towards what I perceive to be widely held assumptions across the political spectrum, which might not always line up with the assumptions of people who care enough to read newsletters.

Polarization?

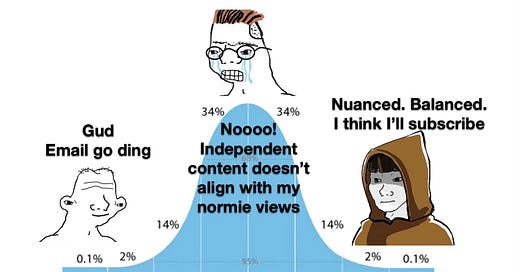

Brian: There are two main types of polarization which are frequently discussed: ideological polarization, or how different Americans’ policy preferences are, and affective, or how Americans react emotionally to those of different political beliefs. Whether ideological polarization is a good or bad thing is quite difficult to discuss without going into specific policy details, so I’ll keep it brief. I believe it leads to more experimentation on net and is a good thing in that regard. There’s a widespread notion that ideological polarization is bad in general, but I think this is a difficult economic question that can’t be easily answered for sure. I definitely believe the confidence with which many political figures say polarization is negative is unjustified.

There are many narratives around affective polarization that try to avoid discussing the issues themselves: people simply need to reconcile their beliefs, have more discussions with the opposing side, be less angry, or stop using social media. The common thread is that affective polarization downstream of irrational factors and a more agreeable politics would be downstream of more rational factors, like increasing the information voters receive and exposing them to arguments from the opposing side. However, research is mixed on both of these questions with (at least in my somewhat biased judgment) most papers favoring increased polarization both among higher information voters and exposing voters to opposing opinions. It is also pretty difficult to square this with the general macro-trend of our current high-information society receiving much greater quantities of information.

An alternative hypothesis is that the underlying issues and circumstances would result in more polarization, which I think is right. Take the issue of COVID lockdowns. The variance in what you were practically able to do circa fall 2021 was enormous between different states alone and difficult to ascribe to anything other than government policies. Moving between states, ending friendships or avoiding romantic relationships to prefer people who agree on this policy actually makes logical sense. Someone who genuinely believes that their friend or partner is cruelly exposing everyone to severe danger would logically avoid them. Similarly, someone in the same situation with a friend spreading paranoia and unnecessary hassle with testing and masks would also benefit their material lives from ceasing contact with the friend. There are many similar circumstances, though perhaps not as extreme, where affective polarization is a reasonable and personally beneficial action. The more Americans realize this, the more their affective polarization catches up to the underlying policy differences.

Info: A lot of polarization seems to stem from becoming rapidly more informed about basic things. In the religious wars that followed invention of the printing press it was, “I can’t believe my neighbors have different beliefs about God, this can’t be tolerated”, today maybe it’s the same with political or cultural views and not being able to stand what those people on the coast or in the middle of the country think about things.

Brian: This raises a good point about the difficulty in defining rationality. Is it rational for Americans to care about the policies, cultural or economic, of people far away, but nonetheless part of the same country? It’s pretty difficult to answer that for the long term.

Expertise?

Brian: I don’t think the primary problem here is people seeing the world as they wish it were. Many people assume that many institutions and experts are competent systems and/or select for the most competent people because this is what is taught in schools and media. In my experience, normal people change their mind fairly often once you present them with counterexamples, so I think it’s more a problem with lack of information rather than idealism. I don’t have that much knowledge on this occurring among the general population, although I should note that trust in media and government have declined. There are other surveys other than this one, but I’m not sure how many you want me to link. This is the most striking one.

Competition?

Brian: I’m not sure what this question is asking for? Competition is quite vague, and there are vastly different assumptions and realities based on the specific type of competition.

Info: I guess I was sort of leading the witness on this one. Coming from an economics background, a common disconnect I see between econs and normies is that most people seem to think that competition is inherently distasteful. They don’t like the thought of some people winning and others losing (outside of some very low-stakes domains like sports) and so they have a sort of anti-market bias for that reason. What they don’t realize, in my view, is that there’s always going to be some form of competition in human affairs and that limiting explicit competition often leads to worse forms of implicit competition, unconstrained by a sensible mechanism.

Brian: I think this analysis is correct, but see it as something different than simply seeing the world as one wishes it to be. There’s a more psychological or evolutionary analysis that looks at the degree of influence some people have in worlds that are, loosely put, more or less honest. Some people are more advantaged in worlds that are less honest, and behaving in ways that make their surroundings more like that world is beneficial to them, at least in the short term. Of course it is reasonable to argue that in the long term economic growth materially benefits them much more than any short term social gains, but very few instincts operate at that time horizon, if any.

Info: I think that leads well into the next topic.

You attribute much of the blame for today’s institutional failure to the “midwit cycle”—incumbent institutions select mediocre people on the basis of conformity, who in turn recruit more mediocre people to strengthen their claim to status, gradually resulting in an entirely new set of internal norms and procedures antithetical to competence and merit.

I might interrogate the broader model a little more in a second, but first how does one know if they are a midwit, and can a midwit do anything to stop being one?

Brian: Much is somewhat vague here, so I should clarify that while I think the midwit cycle is a significant cause of decline, I’m not completely certain on its relative significance. Looking simply at businesses and midwit cycle effects post-scaling, I think it’s fair to assume upwards of 25% of decline in productivity to this effect, as a very low estimate, although it’s quite difficult to come to an exact number in these multifactorial situations.

The technical definition of midwit I use in the article is simply someone with IQ within one standard deviation, typically 15 points, of the average score of 100. This is simply for clear categorization, although obviously much of the analysis is likely to apply to someone of 116 IQ even if they do not fall explicitly within that range. In this narrow definition the midwit category is not really mutable.

The more expansive definition involves the behaviors that are more common among midwits. Social games, prestige, credentialism, conformist activism, et cetera. This is not a one-to-one mapping, since even within iq ranges these behaviors are far from universal. It would be what Max Weber calls a statistical type, or a relationship that is true on average but not universally. This more important but blurrier component can obviously be changed. I would encourage anyone, regardless of IQ, to pay more attention to their social behaviors and try to be less deceptive if at all possible.

I actually don’t think the category is really all that useful for predicting individual behavior. Instead it is a tool for observing what institutions converge to — what they inevitably become after selection effects are applied for enough time. In the case of Google, that time is around 10 years, while for other institutions it may have taken longer or shorter. While it’s very funny to call individuals midwits, I don’t think that translates easily to the institutional analysis in the piece even if it’s technically correct. I wouldn’t worry about being a midwit individually.

Info: In your Edward Teach review, you wrote,

“Someone whose base instinct for dealing with the unknown is to take shoddy models and confidently proclaim them the Rigorous Truth cannot believe in God, or any religion, or metaphysics. You might not like it, but the “Trust the Science” midwits are what peak atheism looks like.”

I find this very provocative, but it’s not fully clear to me where religion fits into your model of the world. Are modern midwits trying to fill a vacuum that has been left by traditional faith or are our institutional structures themselves responsible for killing God? Something else?

Brian: I don’t think this line encapsulates my broader view of religion or atheism, but it’s a funny summary of Nietzsche’s argument which I think actually does it a fair amount of justice. I obviously can’t explain Nietzsche fully in one paragraph. In Nietzsche’s time he would say that the institutions and ways of life are the reason why it has become impossible to believe in God, although scholars still argue about the precise way to interpret him. I don’t want to overstep here, since the reference to Nietzsche is only most important for introducing a parallel to Teach’s later ideas.

My view of religion in the modern day is actually quite optimistic. I feel like that kind of routinized, embodied belief is probably a healthier lifestyle for most people in the coming years, although I can’t fully justify this. I basically buy the argument in George Dyson’s Analogia that technology is becoming less understandable, particularly to the average person, and the golden post-industrial revolution age where the most important problems were all made “understandable” is now over. This marks the stage for a religious revival, although people always predict that now and again with varying degrees of success.

Until rather recently, you wrote under the pseudonym “Cactus Chu”. What convinced you to de-anonymize and how has it changed your experience of writing online so far?

Brian: I more or less answered the first part of this question here. I don’t just believe that being honest with my political views won’t hurt me, but in fact will actively attract interesting people and repel people who I didn’t want to interact with in the first place. I was anonymous at first because I didn’t think about it too much. After considering it, I realized this wasn’t necessary. I don’t think it has changed my public writing that much. I’ve had a few people reach out professionally via linkedin and email, so in my private life it has been slightly positive.

Info: Seems consistent with your views on polarization. Best of luck going forward, and thank you for your time!

I wonder if you or Brian has any thoughts on how the midwit cycle combines with the general antipathy toward competition. I might suggest that one marker for being a midwit is having credentials yet being unable/unwilling to monetize them via market competition. This leads the person to engage in competition in other less productive arenas, like winning status games inside a bureaucracy, which can often have negative economic effects, both in terms of inefficiency (e.g., bureaucratic kludge) and bad policies (e.g. going for diversity over performance)....