Over the past few months, I’ve had the opportunity to compete in a cool new forecasting tournament sponsored by CSPI. They’re still taking entrants here.

The whole thing works kind of like the stock market, but instead of buying shares in companies you expect to rise in value, you can buy yes/no positions on future events.

For example, participants can pay 54¢ for a YES share (or 46¢ for a NO share) that returns $1 in the event that Donald Trump is indicted (or not) before the end of the year. As bets collect over time, prices adjust to reflect the current collective estimate of how likely this is to happen.

But how good are these estimates

Are Manifold Markets Efficient?

One of the most influential theories in economics is the efficient markets hypothesis, which argues that current market prices provide the best available estimates of asset values by incorporating all available information.

While I generally trust this theory when it comes to investing in public equities, I’m less sure it holds up in this particular setting. Here are some reasons to doubt the Manifold Markets being used in the contest:

1. Selected sample

Seeing as this contest is sponsored by two right-leaning think tanks, it’s natural to worry that market predictions will be biased right.1

Representativeness tends not to be a major concern in real-world financial markets because a single participant with enough leverage can arbitrage away any mispricing caused by widespread bias. But given a relatively small pool of participants, limited available assets, and no easy way to leverage on Manifold, I don’t think we can rule out this source of inefficiency entirely.2

2. Skin in the game?

Unlike more established prediction markets, Manifold is based entirely on play money, allocated in equal amounts to each competitor when he or she signs up. The only external incentives to bet wisely are awarded as prizes according to relative rank:

Top five get interviewed for a chance at a $25k research fellowship with The Salem Center

Top twenty get a conference invite from Richard Hanania, Bryan Caplan, and Robin Hanson and may contribute an essay on forecasting

Gold (top 1%), Silver (top 5%), and Bronze (top 10%) distinctions for official bragging rights

These prizes seem pretty great if you love the people involved but might not be enough to discipline the market. Apart from exacerbating the selection issue, a prize system seems better suited for correcting real world market failures than establishing baseline incentives for price discovery.

3. Perverse incentives

In fact, rank-based payouts create significant incentives to bet differently from how you really think. As Noah Kreutter points out,

Financial markets tend to break when participants are optimizing for the probability of finishing in the top N, especially when N is small. If I were trying to maximize my probability of winning this tournament in a blended pool of rational and irrational agents, I would be:

1) taking way more risk than I would if my goal were simply to maximize my portfolio's returns

2) taking risks that give me different risk exposures from other participants, even if the arithmetic expectation isn't in my favor.

For example, if the true probability of an event happening is 90%, and various market participants bid it up from 50% to 88%, well, I am probably more likely to sell it than buy it at those prices. The intuition is that if the event resolves YES, I will have bought it at the worst price among all the people who bought YES, but if the event resolves NO then I will have sold it at the best price among the people who sold YES.

If the contest primarily rewards gaming the system, prices are less likely to correspond to reliable probability estimates.

4. Price slippage

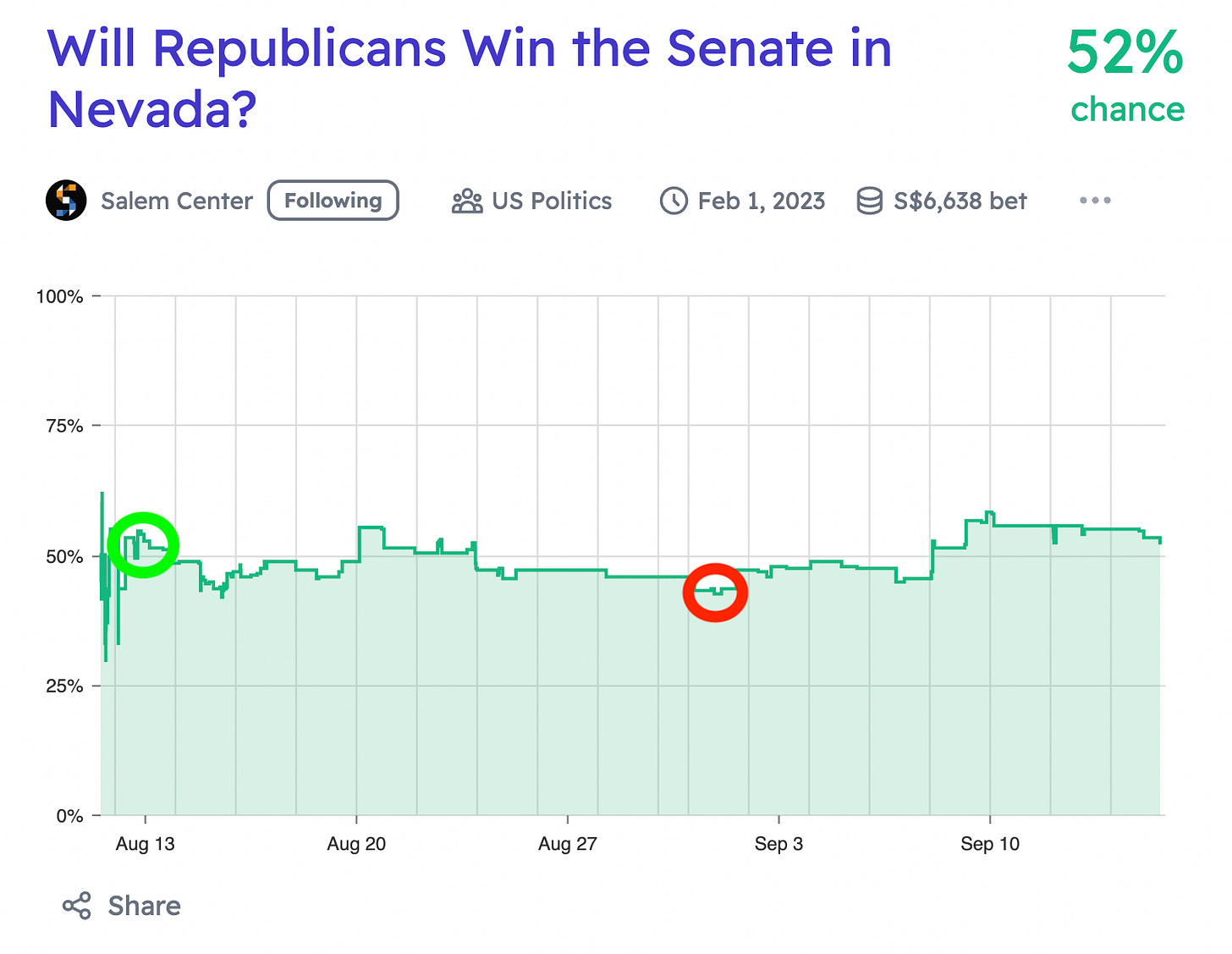

Markets tend to work best when it is easy for market participants to open and close positions without causing large movements in the price. Early in the contest, there were definite problems with this:

Five days into the contest, moderators took note and made some changes to ensure liquidity. As Hanania explained,

After 24 hours, we will add $1,900 in liquidity to stop major fluctuations in market prices, based on the idea that one person should not be able to singlehandedly cause extreme movements. (emphasis added)

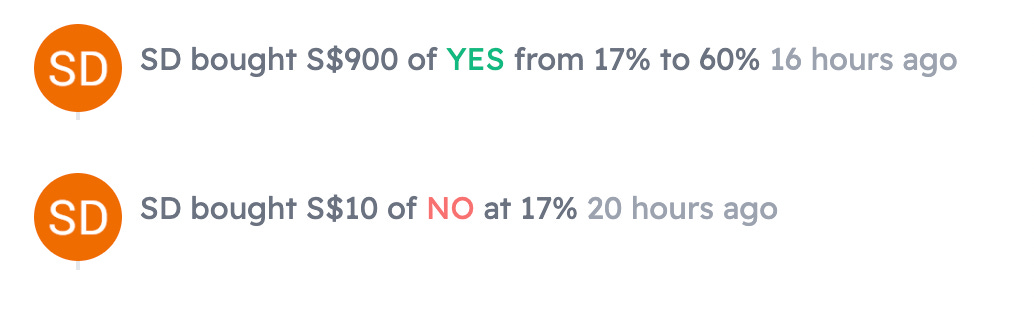

But while these adjustments appear to have improved the market, individual users still have substantial power to shift prices on their own.3

Beating the Market

Suppose I’ve convinced you that this market is inefficient and you’re itching to trade. How exactly should you go about collecting all those dollar bills on the sidewalk?

Based on my experience thus far, here are some strategies that appear to work:

Start with the base rate

While it’s tempting to latch onto the most striking details of an event, you’re more likely to succeed by starting with a very general assessment.

To forecast the November Senate winner in Nevada, for example, I first calculated how often Republican candidates beat Democratic ones using the last several decades of Nevada election outcomes. This number became my base rate probability estimate for a Republican victory.

From there, I incorporated slightly less general information into my estimate such as incumbency status and the tendency for the President’s party to lose seats in midterm elections, followed by the recent polling numbers.

Cross-market arbitrage

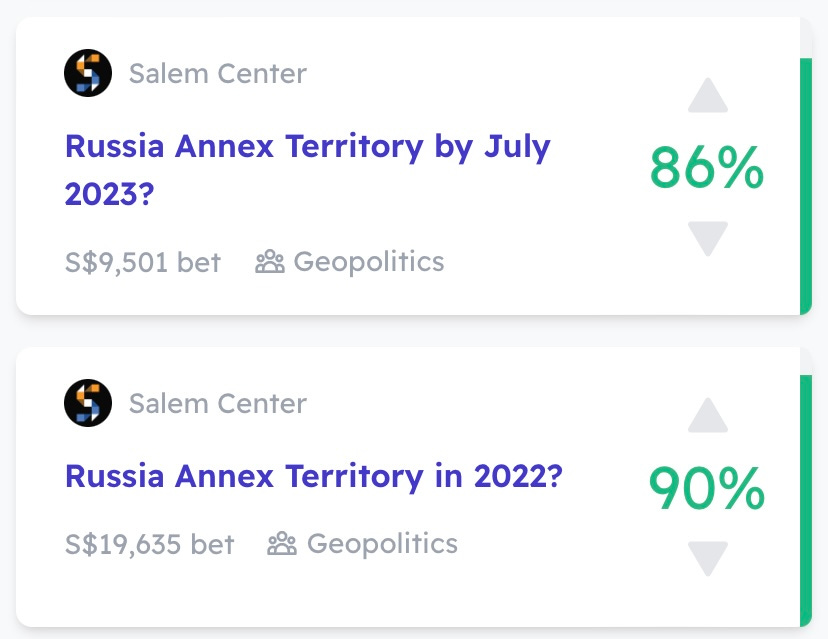

In standard arbitrage, a trader obtains low-risk profit by simultaneously going long and short two similar assets with inconsistent prices. Occasionally such opportunities do present themselves within Manifold.

But while such clear-cut instances of arbitrage are few and far between, it is often possible to identify good bets by observing price differences in comparable securities across different market platforms.

If a market you trust more than Manifold trades identical questions at a different price, you can buy the appropriate shares needed to close the price gap.

You can also consult traditional financial markets profitably. When this screenshot was taken, the option implied probability distribution for WTI oil futures suggested that the price was too high.4

And sometimes non-identical prediction market comparisons still point to clear arbitrage opportunities, as was the case here.5

But a quick word of caution—sometimes forecasting questions are not as comparable as they seem.

Early in the contest, I was almost tempted to wager real money on student debt cancellation based on the assumption that Manifold (top) and Kalshi (bottom) would settle under the same set of circumstances.

If I had bought into Kalshi—reversing my usual tendency to trust real money markets over Manifold—it would have been when the two markets sharply diverged in price just after the peak marked by the red arrow. Biden’s announcement was set to happen at any moment, and the terms really seemed identical by my reading. But it turns out the market read the fine print better than I did—under Kalshi’s interpretation at least, Biden’s debt cancellation didn’t count.

Exploiting price slippage

Another common strategy involves using limit orders, which automatically buy yes/no shares at a predetermined price. Should the market rise or fall to the contracted level, Manifold will exchange shares for Salem dollars in your account.

This can pay off extremely well when erratic price fluctuations pop up, either from overreaction to news or new entry by participants looking to get a lucky break placing all their money on a single bet. But if you’re not able to monitor breaking news closely, this is risky—sometimes event fundamentals can make truly rapid shifts.

Since I don’t always have time to hop in and cancel no longer favorable limit orders the way some market participants seem to, I tend to be somewhat conservative with this strategy. But even if you only use this tool to avoid the transaction costs accompanying quick buys, it can make a difference over time.

Market manipulation

Some market participants try to use Manifold’s comment feature to their advantage by selectively providing information favorable to their position. While I mostly try to abstain from engaging in this myself, I don’t entirely ignore it either.

Ranked from best to worst, there are four rough tiers of market comments:

Verifiable Facts

Anecdotes/Speculation

Possibly Deliberate Misinformation6

Childish Bullying

While I mainly included this strategy for fun, I think there’s some value to be picked up here. I’ve made some profit by following users that show their work, and the other antics help identify participants to be extra skeptical of. In extreme cases, I even consider betting against such traders if they drop too much money at once on a question.

Closing Thoughts

So how did I do using these strategies? Was I able to rob the market blind and become a master of arbitrage?

For the most part, the answer is no. While I’ve improved on my initial endowment by a few hundred dollars, nearly all of my winnings trace back to the first few weeks of the contest. Because only a few participants had joined and the most foolish traders had available funds on par with the smartest, it was relatively easy to find profit opportunities.

Since that time, the best traders have compounded their winnings and act quickly to remove mispricing using automated news alerts and pre-planned limit orders. Many of my strategies are hardly worth the time needed to implement anymore because at the end of all the base-rate setting and option price calculating I often end up with a number remarkably close to the current market price.

As much as it hurts my pride to admit, my best bet for reaching the top five is probably to start taking a lot more risk and hope I get lucky.

Of course, there are many other possible sources of bias due to participant selection. For instance it is highly likely that a randomly chosen participant is American.

Last I heard, there were less than 500 participants and many showed limited engagement (e.g. less than half completed the survey required to be eligible to win). I suspect many more people may have joined since then, but it’s hard to tell for sure.

It is technically possible to obtain some leverage if multiple limit orders fill at the same time (as might happen following a large price swing). Once the order (or partial order) pushing you negative goes through however, all remaining limit orders are cancelled and you can’t resume betting without closing existing positions.

My convention for anonymizing screenshots in this post is to only block out user information that may be identifiable. If you appear in an unedited screenshot and would like me to block out your username send me a DM here.

The link presented as evidence was completely speculative and in context of other observed behavior seemed fishy. But to be charitable, they may have just been irresponsible in latching onto the rumor.

The strategies you are proposing are Too low variance to actually work. Your srategies will result in a very high probability of not finishing top 5.

The optimal strategies are

1. the HFT strategy

Have No life

have news alerts

Whenever news that would significantly shift a market happens wager a lot on that shift

wait for others to catch up to the news

Sell

2. The YOLO strategy

Find poorly priced options

wager everything using limit orders

Win contract and repeat x10

It is important to note that arbitraging the 2 UKR war dates is a losing strategy, by doing that you are blundering since the resolution date of those 2 options is way way too far in the future to matter. the optimal strategy is to parlay like a madman and to do that resolution date is teh most critical thing.