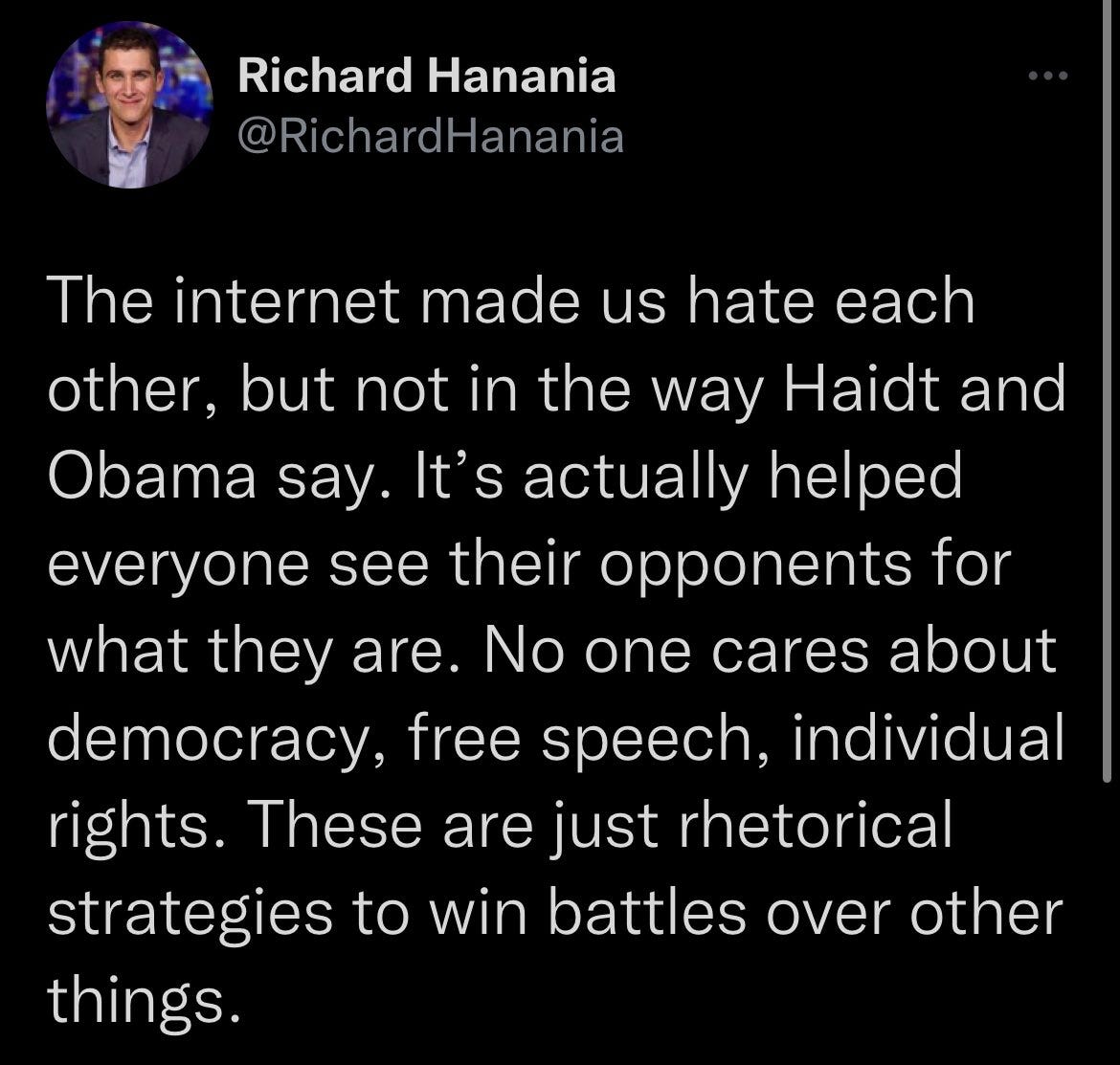

Richard Hanania doesn’t shy away from the culture wars. To first approximation, his promotional strategy seems to involve offending someone with every tweet.

But while there is no shortage of trolls on the internet, Hanania is more reflective than most.

In “Why Do I Hate Pronouns More than Genocide?”, he explains why he fights—even when it’s not pretty.

II.

Those who hate white people are convinced that they’re actually worried about police brutality, just like those who dislike foreigners have convinced themselves that tariffs make the country better off, and people who are jealous of the rich pretend as if their activism is about helping the poor.

Sometimes my own politics come down to “I just hate X, and like Y.” But when that happens, I want to be honest about it, both to myself and others.

Start with the view that humans are hypocritical. If you ask someone why they do something (e.g. support policy X), they will often give a good reason for supporting X. But it will not be the real reason.

Hanania believes that the real reasons behind what we do are far less flattering than the story we tell ourselves. He discusses these motivations in terms of two broad categories, ego gratification and aesthetic preferences, along with their implications.

In the process, he attempts to avoid the dishonesty he sees as part and parcel of politics by ruthlessly identifying the unflattering motives behind his own choices.

III.

Many of Hanania’s insights echo a central theme from Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler’s The Elephant in the Brain—human action is fundamentally motivated by an unspoken desire for status. The authors write,

Our minds aren't as private as we like to imagine. Other people have partial visibility into what we're thinking. Faced with the translucency of our own minds, then, self-deception is often the most robust way to mislead others. It's not technically a lie (because it's not conscious or deliberate), but it has a similar effect. "We hide reality from our conscious minds," says Trivers, "the better to hide it from onlookers.”

This insight resolves a seeming paradox of human behavior. While people are plainly hypocritical (their words do not match their actions), for the most part they are also sincere. The Hansonian/Simlerian view is that humans evolved powerful faculties for self-deception to facilitate status-seeking without being aware of their true motives.1

In politics this manifests as moral outrage directed toward causes of dubious social value. Though genuine crimes against humanity abound, left-wing media is more prone to focus on things like insufficiently progressive reading lists in obscure southern school districts while right-wing media does the same for woke textbooks in Florida.

Though this is hard to justify from the standpoint of objective morality, it makes sense if people are primarily motivated by ego gratification. Hanania explains,

So what is it that is driving [instinctive] morality? I think it’s based in part on the story we tell ourselves about our lives and our relationship with the rest of society. We want relative status, and to feel better than other people. Emotionally, I don’t identify with the tribe of “people who don’t commit genocide.” That tribe is way too large to provide me with relative status, and doesn’t even particularly appeal to any of my inherent strengths. In this theory, “status” can be only in one’s own mind, as for me I’m very willing to say things that I think are true even if they are unpopular as long as I think I’m right.

Because belonging to the tribe that reserves moral outrage for broadly agreed-to-be bad things like homicide and war crimes doesn’t satisfy the human need to feel special, people choose groups small enough to provide differentiation and large enough to provide useful allies.

Democrat/Republican often works fine for this purpose, but note how this affiliation tends to fluctuate with the size of the relevant population. In times of war, shared American identity becomes a source of relative status with both D’s and R’s defined against foreign enemies. Here partisans are not transcending their pettiness to address a higher-order collective goal but simply adopting different tactics for gratifying the same base instincts that drive their politics in other settings.

Viewed in this light, attempts to tackle big societal problems (Covid-19, climate change) by conceptualizing them as the common enemy of man are unlikely to succeed. A better bet is to award high status to productive individuals and teams (Moderna, Elon Musk) that produce results.

IV.

Hanania also assigns a central role to aesthetic preferences, a term which I was not much familiar with before writing this essay. In philosophy, aesthetics concern the judgments we make at a sensory level—how we distinguish beauty from ugliness, harmony from discord, the holy from the profane. Often these judgments manifest in strong, involuntary emotions like humor or disgust.

As with status motives, people often attempt to justify their aesthetic preferences in terms of reason without being fully aware they are doing it. They confabulate.2

Whenever a plus-sized model is put on the cover of Sports Illustrated or Vogue, conservatives start screeching about “glorifying obesity.” These are the same people that giddily mocked the Obama administration’s healthy lunch program, and show no interest in public health measures until forced to look at fat women in swimsuits.

Hanania disdains this kind of post-hoc rationalization but sort of doubles down on the aesthetic preferences themselves. In lieu of decisive empirical arguments to refute one of his strongly held views, he believes leaning on aesthetics is legitimate.

But even if I was convinced it couldn’t [be justified by utilitarianism], and someone proved to my satisfaction that, for example, encouraging children to explore their gender identities at a young age would somehow lead to a happier and healthier society, I would still oppose it. My mind could probably be changed if it turned out that the benefits of teaching kindergartners gender theory were truly massive, say a doubling in GDP growth, indefinitely compounded over time. Barring that, I’m happy to go with my instincts.

This perspective subverts many of the ideals I grew up associating with politics and debate. For example, while none of my teachers doubted that people deviate from rational thinking, there remained an expectation that policy positions be defended with something resembling a reasoned argument. You couldn’t simply “like X and hate Y”.

By contesting such norms on grounds of hypocrisy, Hanania leaves little room for compromise or persuasion. Political discourse is ultimately a battle for dominance.

V.

For me, this essay brought into focus three of Hanania’s core views:

Politics is unavoidably driven by emotion and ego-gratification

Aesthetic preferences are a valid impetus for political action, despite being largely arbitrary

Hypocrisy is contemptible and those who practice it should be lowered in status

While I am sympathetic to aspects of each individual claim, I have misgivings about the political culture that might follow from fully internalizing them.

In particular, I am concerned by the prospect of a right-wing whose defining value is “hatred of hypocrisy”. While it is often necessary to clearly communicate what is wrong about something in order to fix it, channeling emotional energy toward condemning hypocrisy is likely less productive than seeking out a positive contribution. Instead of reveling in the ways the system is broken, we should look to build new institutions and shore up the good in the ones we have.

Truth be told, if I could wave a magic wand and create a world without hypocrisy I’m not sure that I would. My own aesthetic sensibilities incline toward aspirational ideals that admit space for a man’s reach to exceed his grasp, and I worry that the easiest way to avoid hypocrisy is to never espouse any principles at all.

At any rate, economics suggests that we should be hesitant to declare something categorically good or bad and instead ask “at what margin?”. No matter how strong our gut-level aversion to it might be.

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz’ Don’t Trust Your Gut (which I reviewed here) provides a concrete illustration of how self-deception can facilitate status-seeking.

“A groundbreaking 1947 study by Harold T. Christensen did just that. Christensen surveyed 1,157 students and asked them to rate the importance of twenty-one traits in a potential romantic partner. The number one, single most important trait reported by both men and women was “dependable character.” Right near the bottom for both men and women, the traits they said they cared about least, were “good looks” and “good financial prospects.”

As SD notes, these self-reports are overwhelmingly contradicted by daters’ actual actions, which suggest that money and appearance are highly valued in dating. The Hanson/Simler interpretation of these results would stress that (1) it is easier to successfully attract a beautiful and wealthy partner if you can convince them you love them for other reasons and (2) the easiest way to do this is by believing it yourself.

Here Hanania gives an example of this in the context of trans athlete participation in women’s sports:

“Liberals discredit themselves by denying the male advantage in sports, or using fake social science and statistics to downplay sex differences. A more honest liberal case for trans women in sports should go something like this:

The justification for funding and supporting women’s sports beyond what there is actual demand for is feminism. We want girls growing up having ambitions, opportunities, and interests that are as similar as possible to men’s. That’s why we don’t care about men who are too weak or uncoordinated to make sports teams, or women in the same boat; what matters is that males and females play sports in similar numbers so we have equality across the sexes. We now believe in trans-inclusivity, meaning that we do not want society to treat cis women and trans women any differently. That being the case, there is no justification for keeping trans women out of female sports; doing so stigmatizes them and implies that they are somehow not “real women.”

And:

The politicians and pundits most interested in “saving women’s sports” from trans participation are those least interested in issues like equal pay and government support for female athletics.

An honest case against trans women in sports, from the conservative perspective, would look like this.

We believe that there are only two human genders, males and females are naturally different, and society, culture and law should reflect an acceptance of and comfort with those differences. Trans women in sports implies that gender is a choice, and that those with XY chromosomes are anything but boys and men. We think this is an unhealthy trend, and want to draw a bright line saying that gender is determined by biology, not choice or subjective “identity.”

Thanks for the essay. I'll add that I think my dislike of hypocrisy can be seen as subset of dislike of BS more generally. This is why I hate economic central planning, experts, US global empire, and civil rights law, while respecting results-based science, markets, including betting markets, Nassim Taleb, and the international balance of power.

Moreover, I don't think hypocrisy should play no role in society. I think it's to a large extent unavoidable. I dislike the leftist variety because it's harmful and the one with the highest status. I don't care about say the hypocrisy of traditionalists because I'm more sympathetic to their outlook and it doesn't have as much power. If Christian conservatives had as much power as LGBT and vice versa, I could take a different view. It's the combination of high status + harmful that makes some particular hypocrisy worth attacking.

Also, I wouldn't say aesthetic preferences are arbitrary. I think there's a human nature that's being subverted in unhealthy ways. But I don't worship human nature as a guide to policy, there's an egalitarian instinct that's worth suppressing because it leads to socialism and economic redistribution, which is harmful for human progress. This is the inverse of some liberals, who acknowledge that say homophobia and ethnocentrism are part of human nature but think they should be fought anyway, while humans can justifiably indulge the preference for equality. I think it's the preference for equality that is our greatest sin. I also dislike ethnocentrism and racism in certain cases and think these things in most periods of human history have gone too far, but today in many ways we've overcorrected.

Robin Hanson would probably agree that abolishing hypocrisy would be bad, since homo hypocritus has accomplished so many amazing things. But prediction markets which penalized hypocrisy and rewarded accuracy would be even better.