Workers of the World Unite!

Is the labor shortage a collective action problem?

During the earliest months of the pandemic, employers couldn’t downsize fast enough. Millions were laid off, executives took symbolic pay cuts and ordered wage and hiring freezes, and many economists predicted a grim year ahead for workers hoping to just get their old jobs back, never mind get ahead.

Eighteen months later, U.S. employers are struggling to fill 10 million jobs and many of those same workers are looking at the offerings and saying, “No, thanks.” Since April of this year, Americans have quit their jobs and not returned to the workforce at a historic rate, an exodus some call “The Great Resignation.”

Why do so many jobs remain unfilled? Presumably some workers are still reluctant to work due to concerns about the virus, while others have been able to rely on generous relief payments and unemployment insurance. 1 Decreased access to child care and increased immigration restrictions are other plausible factors.2

Still, the present moment is without clear precedent and none of these explanations seem fully satisfying as an explanation of the labor shortage. This has lead some to wonder whether we are seeing a once in a generation change in worker activism—a “take this job and shove it" moment as economist Larry Katz describes it. Under this theory, the pandemic has caused workers to realize that they were always getting a raw deal and gave labor the leverage it needs to fight for better treatment. Perhaps the extraordinary ordeal of the last 18 months has even rewired workers’ brains in a way that has made them recognize the true worth of their services.

While Marxists have long held out hope that laborers would rally together to defeat the capitalists, I am skeptical that Covid-19 is a glorious solution to some age-old collective action problem. I would look instead to indicators that suggest that work conditions have been uniquely bad during the pandemic, as longer hours, additional protocols to follow, and a dearth of coworkers to lighten the load contribute to greater incidence of burnout.

According to Harvard Business Review, those resigning at the highest rates have been primarily concentrated in sectors which have experienced the most extreme increases in demand over the past year, suggesting that these workers are indeed facing unusual workloads contributing to burnout.3 Moreover, the ages filing the most resignations line up with generations reporting the highest level (Millennials) and growth rate (Gen X) of burnout.

Ironically this state of affairs creates its own kind of collective action problem. If 10 million people were to step forward all at once to fill the job openings available in our economy, they could all benefit by earning paychecks without having to bear unmanageable workloads. For workers making the decision alone however, returning to current working conditions is a daunting proposition.

Author’s note (12/7/2021): Short summary here and Arnold Kling comments

Even now, real disposable income remains higher than it was prior to the pandemic:

Though probably not as much as you might think in the case of child care:

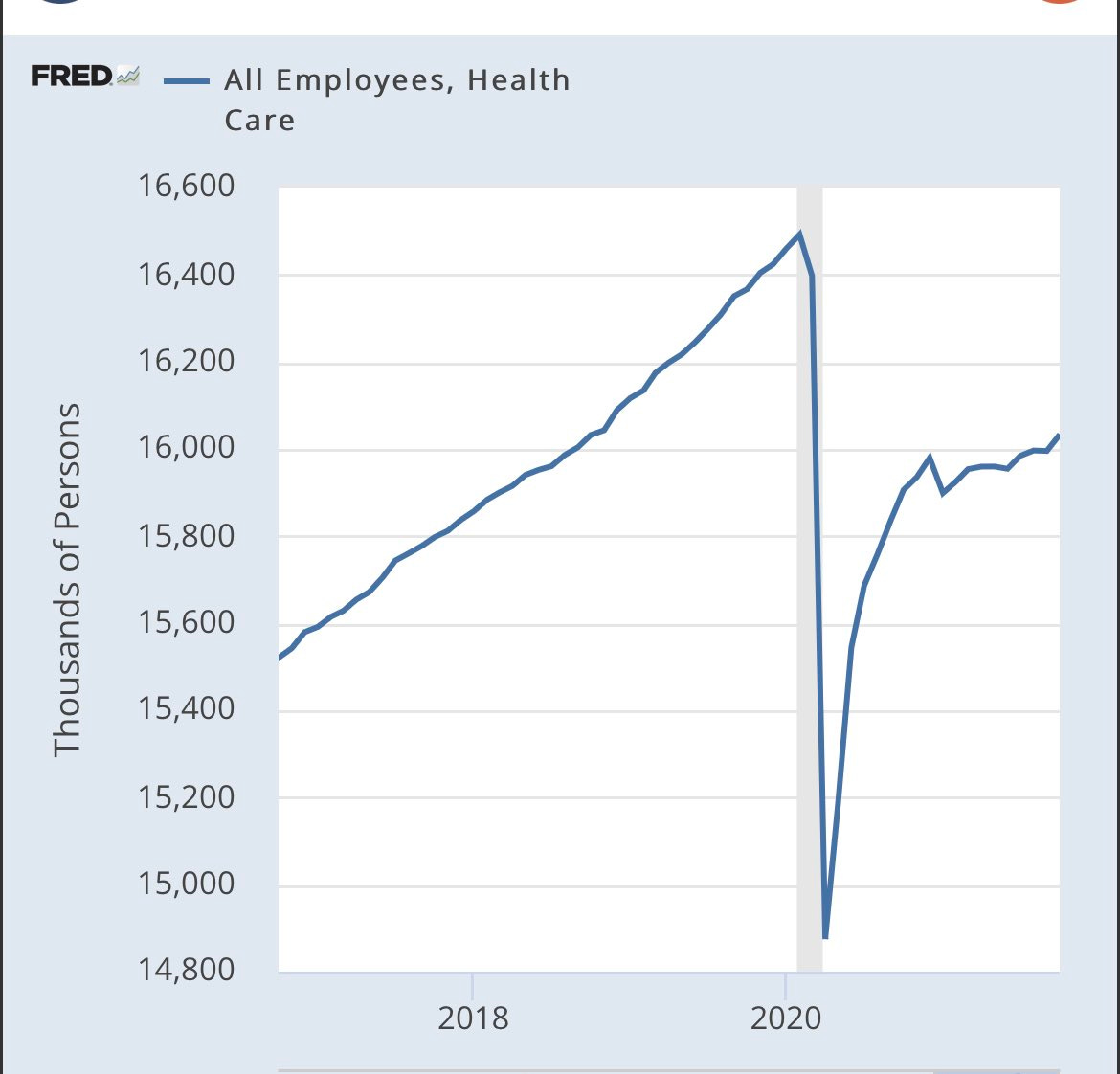

See healthcare for example, which has a large employment shortfall and a 3.6% higher quit rate relative to last year.

Great article! I think you lay it out really well. “True worth of their services” is an interesting phrase. Many people were laid off and called “non-essential” workers.

Great graphs, especially the one showing that with gov't support, the disposable income actually increased. Massive and continuing Gov't benefits is likely the main reason, tho rethinking rat race career choices seems also likely for many - including new homeschooling mothers.